Azithromycin (i.e. Zithromax) is an antibiotic used to treat various bacterial infections (gram-positive, gram-negative, and atypical).

Azithromycin is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, costs about $4 for a standard course of treatment, and remains one of the most-prescribed antibiotic medications in the United States.

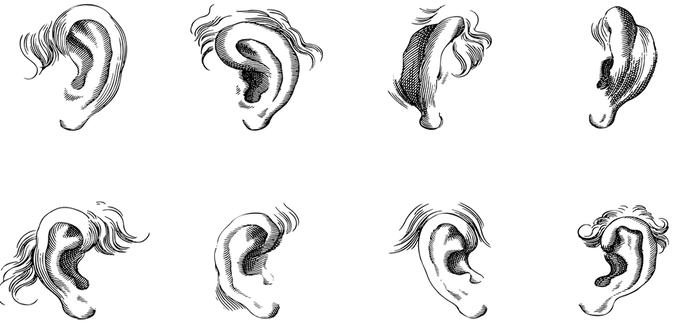

Despite the fact that azithromycin is extremely safe (relative to other antibiotics), all users should be informed of the fact that, in rare cases, azithromycin causes hearing loss, ototoxicity, and/or tinnitus (ringing in the ears).

Onset of Azithromycin Hearing Loss

Onset rate of azithromycin-related hearing loss after treatment initiation is unpredictable and variable among users. (R)

Select individuals exhibit rapid-onset azithromycin hearing loss – evidenced by hearing loss and/or tinnitus within hours or days of treatment initiation. (R)

Other individuals exhibit delayed-onset azithromycin hearing loss wherein hearing loss and tinnitus emerge after weeks or months of treatment initiation. (R)

Theoretically, hearing loss could occur after stopping azithromycin due to the fact that the medication has a long half-life (68 hours) and remains in systemic circulation for 15.58 days post-cessation. (R)

Characteristics of Azithromycin Hearing Loss

Common

High-frequency. Most cases of azithromycin-related hearing loss present as high-frequency hearing loss. (R)

Bilateral & symmetric. Azithromycin tends to cause bilateral and symmetric hearing loss wherein both ears are affected equally or evenly by the losses.

Usually reversible. Most individuals with azithromycin-related hearing loss report hearing improvement or complete recovery once the medication is discontinued. (Prompt azithromycin discontinuation, corticosteroid treatment, and antiviral therapy increase odds of hearing recovery). (R)

May be accompanied by tinnitus. Tinnitus, the perception of ringing, buzzing, or humming sounds, has been reported before the onset of and after azithromycin-related hearing loss.

Gradual deterioration. Progression of azithromycin-related hearing loss is thought to be gradual whereby one might experience initial tinnitus or hearing loss – then experience no additional hearing deterioration for weeks or months thereafter.

Less common

Irreversible. Certain individuals will experience irreversible (i.e. permanent) hearing loss and/or tinnitus as a result of azithromycin ototoxicity wherein hearing does not improve following prompt azithromycin discontinuation, corticosteroid administration, and antiviral use.

Asymmetric. Azithromycin-related hearing loss may occasionally affect one ear more significantly than the other – as evidenced by various case reports (e.g. mild-to-moderate loss in one ear – and moderate-to-severe loss in the other ear).

Speech & low-frequency. Select cases of azithromycin-related hearing loss may present as inability to understand general speech and lower frequencies. (R)

All frequencies. Rare cases of azithromycin ototoxicity may present as hearing loss that encompasses all frequencies (high, mid, low). (R)

Rapid deterioration. Select individuals may experience rapid deterioration of hearing after onset is noticed – such that hearing profoundly deteriorates within a short-term (e.g. hours or days) following onset.

Signs & Symptoms of azithromycin-induced hearing loss

Unable to hear high frequencies. Many people have high-frequency hearing loss for reasons besides azithromycin (e.g. aging, noise exposure, etc.). However, if you suddenly notice that you’re unable to hear higher frequencies (relative to pre-treatment) – this is a sign of azithromycin ototoxicity.

Difficulty understanding speech. Select individuals report difficulties understanding human speech while using azithromycin. If you find yourself unable to understand speech (relative to pre-treatment) – this is a sign of azithromycin ototoxicity.

Tinnitus. An extremely common sign that azithromycin ototoxicity has occurred is tinnitus or ringing in the ears. Some people might report buzzing, crackling, or humming sounds instead of ringing. (Not all cases of azithromycin ototoxicity are accompanied by tinnitus).

Muffled or distorted sounds. If speech, music, and/or everyday noises sound muffled or distorted (relative to pre-treatment) – this is a sign of azithromycin ototoxicity.

Fullness sensation. Some individuals will report that their ears feel “full” or “plugged” (in the absence of canal obstruction) as a result of sensorineural hearing loss.

Painless. Most cases of sensorineural hearing loss are completely painless.

Risk factors for hearing loss on azithromycin

Daily azithromycin use. Daily administration of azithromycin is associated with increased risk of hearing loss – relative to intermittent administration. (R)

High-dose azithromycin. Though any dose of azithromycin can cause hearing loss, higher doses are associated with greater risk. High doses yield greater average peak serum concentrations and longer area under the concentration time curve (compared to low doses).

Long-term use. While case reports have highlighted hearing loss following acute/short-term azithromycin use – hearing loss is more likely to occur among long-term users. Research by Li et al. suggests that hearing loss is most likely to occur after ~1-year of azithromycin use. (R)

Renal impairment. Individuals with renal impairment are at greater risk of hearing loss from azithromycin than persons with normative renal function. Diminished kidney function can elevate peak serum concentrations and area under the curve of azithromycin whereby it could become toxic to the ears.

Concurrent substance use. Simultaneous use of various pharmaceutical medications (including other antibiotics), drugs (legal, illicit, over-the-counter), alcohol, and/or dietary supplements – may increase your risk of hearing loss while using azithromycin. Other substances might lower the threshold of azithromycin required to induce hearing loss (via affecting its pharmacokinetics) and/or act synergistically with azithromycin to damage the auditory system.

Certain medical conditions. Certain medical conditions may increase risk of hearing loss on azithromycin, including AIDS/HIV and autoimmune disorders. These conditions may affect the inner ear wherein the inner ears are more vulnerable to toxicity from standard doses of azithromycin. Moreover, flare-ups of various medical conditions may synergistically damage the ear along with azithromycin.

Low BMI (relative to dose). A low BMI (body mass index) relative to azithromycin dose may increase risk of azithromycin toxicity. Low BMI with a standard or high azithromycin dose provides a smaller, more concentrated area for azithromycin distribution/saturation – and elevates peak serum concentrations and area under the curve. As a result, azithromycin concentrations may be more likely to reach ototoxic levels and damage the inner ear.

Severe infection. Severe infectious diseases may increase one’s risk of azithromycin-related ototoxicity and hearing loss. Severe infections might: (1) require elevated azithromycin doses and/or multiple antibiotics simultaneously; (2) directly inflict damage upon the cochlea and cochlear nerve; (3) trigger inflammatory responses that affect the ears; (4) release endotoxins during treatment that damage the ears – all of which could: (A) increase susceptibility to azithromycin ototoxicity and/or (B) synergistically induce ototoxic reactions with azithromycin.

Older adults. Some data indicate that older-aged individuals (65+) are at greater risk of azithromycin-related ototoxicity and hearing loss than younger azithromycin users. (R) This could be because older azithromycin users are more likely to exhibit renal impairment or changes in azithromycin pharmacokinetics – relative to younger persons. Older azithromycin users are also more likely to have preexisting medical conditions and use concurrent medications that might increase odds of azithromycin-related hearing loss. Moreover, aging induces structural changes throughout the inner ear and reduces antioxidant responses – all of which might increase susceptibility to azithromycin hearing loss.

Chronic or loud noise exposure. Azithromycin and various medications are hypothesized to lower the threshold of noise required to induce permanent hearing loss. Some experts like Neil Bauman (PhD) speculate that slightly louder sounds – that wouldn’t normally damage the ears – can damage the ears while under the influence of medications like azithromycin. For this reason, chronic or regular exposure to noise (especially if moderate or high decibel) may increase likelihood and/or magnitude of hearing loss while on azithromycin. Azithromycin and noise exposure may be synergistic in hearing loss induction.

Smoke exposure. Research suggests that there’s a strong link between smoke exposure (e.g. cigarette smoking) and hearing loss – at both speech-relevant and high frequencies. Though it’s unclear as to whether smoking increases susceptibility to azithromycin-related hearing loss – it warrants consideration.

Nutrient deficiencies. Vitamin/mineral deficiencies may increase risk of azithromycin ototoxicity and hearing loss. Many vitamins/minerals help protect inner ear structures and often promote repair following insult from noise, chemicals, and infection-related inflammation or oxidative stress.

High stress & poor sleep. High stress and poor sleep may alter blood flow to the ears, trigger inflammation, induce vitamin/mineral imbalances, and impair endogenous antioxidant responses (e.g. glutathione production). Persons unable to manage stress and/or get adequate sleep may be at greater risk for azithromycin-related ototoxicity and hearing loss.

Gene expression. Research suggests that having certain genes may increase one’s risk of developing antibiotic-related ototoxicity. For example, mitochondrial 12s rRNA mutation A1555G is associated with higher risk of aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Though studies haven’t examined whether specific genes increase risk of developing azithromycin ototoxicity – it’s reasonable to suspect that genes could play a role. (R)

Continuing azithromycin after hearing change(s). Anyone who continues azithromycin treatment (especially for a long-term) after detecting hearing loss and/or tinnitus is at high risk of developing more severe, potentially-irreversible, hearing losses.

Rates of azithromycin hearing loss

Rates of hearing loss associated with short-term azithromycin therapy are estimated at 38 cases per 10,000 patient years. (R1, R2)

In fact, some researchers suggest that azithromycin does NOT cause hearing loss when used for a short-term in healthy adults. (R1, R2)

Other evidence suggests that azithromycin may cause ototoxicity, hearing loss, and tinnitus in a small percentage of users. (R)

An analysis by Li et al. of long-term RCTs reported hearing impairment in 148/895 (16.5%) of long-term azithromycin users 116/866 (13.3%) of long-term placebo users; differences weren’t statistically significant. (R)

Note: Azithromycin-related hearing loss may be: (1) unrecognized by a significant number of patients and clinicians OR (2) misattributed to another cause (e.g. infection) – such that actual incidence rates are greater than reported in literature. Azithromycin-related hearing loss may also be underreported in clinical trials due to selective omission of data by pharmaceutical companies.

Detecting azithromycin hearing loss & ototoxicity

It may be unnecessary for persons receiving short-term azithromycin therapy (e.g. a 5-day treatment) to examine hearing due to the fact that hearing loss from azithromycin is more common among those receiving long-term azithromycin therapy (e.g. 6 months, 12 months, 18 months).

Baseline audiological examination

- Prior to treatment with azithromycin, it is recommended that all patients receive a baseline audiological examination.

- Without a baseline audiological examination, it’ll remain unclear as to whether azithromycin treatment might’ve caused hearing loss – or if hearing loss was present pre-azithromycin.

- It is recommended that audiologists examine hearing ability at all frequencies, especially high frequencies, before azithromycin treatment – as the highest frequencies tend to be affected first when hearing losses occur.

- Because many audiologists may not test for the highest (audibly detectable) frequencies – you may need to put in a special request.

Follow-up audiological examinations

- At various intervals throughout long-term azithromycin therapy, it is recommended to receive follow-up audiological examinations.

- Depending on the total duration of azithromycin therapy, patients may want follow-up audiological testing every: month, 3 months, or 6 months.

- Gwen Huitt (MD) and expert on mycobacterial infections recommends hearing tests at least every 6 months during long-term azithromycin therapy. (R)

- If patients subjectively notice changes in hearing throughout treatment – follow-up audiological testing should be immediate.

- Follow-up audiological examinations may help detect early changes in hearing (particularly within high frequencies) before consciously noticed by patients.

- If hearing changes are detected early via follow-up audiological tests, patients can discontinue azithromycin (and potentially receive corticosteroids and antivirals) in attempt to reverse and/or prevent [further] damage.

- Early detection and appropriate medical intervention (e.g. azithromycin cessation, corticosteroids, antivirals) could decrease likelihood that the hearing loss becomes irreversible.

At-home examinations (Self-tests)

- Various websites and mobile phone apps are available for at-home hearing tests.

- Though at-home testing shouldn’t replace a professional audiometric examination, patients may want to use at-home testing to augment other detection efforts.

- At-home testing is beneficial because (1) patients can examine hearing as frequently as is desired AND (2) it’s completely free (unlike professional exams which can cost hundreds of dollars).

What if hearing changes are detected on azithromycin?

Below are things I’d do – notes to myself. None of this is medical advice.

Discontinue azithromycin

The first thing to do if signs of hearing loss are (subjectively) noticed while using azithromycin is to discontinue treatment.

Azithromycin has a long half-life (68 hours) – so discontinuing immediately at the first sign of hearing loss is imperative to increase odds of hearing recovery.

Seek emergency medical care

Do NOT hesitate to seek emergency medical care if you experience (subjective) hearing loss while using azithromycin.

A medical doctor, or preferably an otolaryngologist, will examine your ears and may initiate treatment with corticosteroids and/or antivirals in attempt to reverse the loss.

You will likely be referred to an audiologist to determine the frequencies affected and magnitude of losses.

Corticosteroids and/or antivirals

In some cases, you may need to request corticosteroids and/or antivirals from a medical doctor (after discontinuing azithromycin) in attempt to restore hearing.

It’s unclear as to whether these agents actually enhance recovery from azithromycin-related hearing loss (as most cases reverse upon azithromycin cessation), however, they shouldn’t hurt.

Dietary supplements

Administration of supplements or supplement combinations with otoprotective properties (e.g. vitamins A, C, E + magnesium) may increase likelihood of recovery from azithromycin-induced hearing loss.

Discuss supplementation with a medical doctor to ensure they won’t interact with other medications you’re using.

Healthy diet & lifestyle

Consuming nutrient-dense foods, managing/avoiding stress, getting adequate/quality sleep, abstaining from alcohol/smoking – may increase your odds of hearing recovery following azithromycin-induced hearing loss.

Avoid various substances

Certain seemingly benign substances (e.g. ibuprofen, caffeine, etc.) may cause and/or interfere with hearing recovery following azithromycin-related hearing loss.

Audit all substances that you ingest on a regular basis and avoid all medically unnecessary substances that are linked to hearing loss.

Infection management

Although you’ll want to discontinue azithromycin in the event of hearing changes, you may immediately require an alternative antibiotic to manage or treat your infection.

You’ll want to ask a medical doctor whether you should: (1) initiate treatment with another medication OR (2) reinstate azithromycin following hearing recovery.

How to reduce risk of azithromycin hearing loss (Hypotheticals)

Below are strategies I hypothesize may help decrease risk of azithromycin-related hearing loss.

Keep in mind that these are merely my hypotheses – they are not guaranteed to help.

Organ function tests (pre-treatment)

Azithromycin is filtered and cleared from the body via the kidneys.

In patients with kidney dysfunction, peak azithromycin concentrations may reach abnormally high levels and remain high for excessive durations – each of which could yield toxic reactions (e.g. ototoxicity).

Azithromycin treatment should be avoided in persons with impaired renal function – and perhaps also in those with impaired hepatic function (especially if concurrent, hepatically-metabolized meds are administered).

Minimal effective dose

The dose of most substances usually determines whether it’ll be toxic and/or the degree of its toxicity.

Though hearing loss can occur from low-dose azithromycin, the goal should be to use the lowest dose required to eradicate your specific infection.

Higher doses (especially relative to one’s BMI) may increase risk of toxicity.

Discuss dosing options with your doctor – but NEVER take less than what’s prescribed because lower doses might not kill certain infections and/or may induce bacterial resistance.

Limit treatment duration

Evidence suggests that longer-term azithromycin use is associated with higher rates of hearing loss than shorter-term use.

Though most medical doctors prescribe azithromycin for appropriate durations based on the specific infection it’s being used to treat – it doesn’t hurt to double check (and confirm) that treatment duration isn’t unnecessarily lengthy.

Avoid daily use (if possible)

Sometimes medical doctors give patients the option between taking azithromycin daily versus intermittently (e.g. M, W, F).

Though doses may differ between daily and intermittent protocols (e.g. 250 mg/daily vs. 500 mg/M, W, F) – evidence suggests that intermittent use is associated with lower rates of hearing loss than daily use (even when higher doses are used intermittently).

Seek emergency medical care at first sign of hearing loss

Azithromycin should be discontinued at the very first sign of hearing change(s) like: inability to understand normal speech, sensation of ear fullness, ringing in the ears, etc.

Additionally, emergency medical care should be sought following initial hearing change to: (1) potentially treat the hearing loss (e.g. with corticosteroids and antivirals) AND (2) determine whether azithromycin alternatives are available to manage the infection(s) for which it was prescribed.

Avoid simultaneous administration with other substances

Though some medical conditions require simultaneous administration of azithromycin with other medications – others do not.

Research suggests that simultaneous administration of medications may increase risk of, or magnitudes of, medication toxicities – relative to “sequential” administration (e.g. administering one medication hours before or after the other).

Protect your ears

While using azithromycin, it is hypothesized that the ears are more vulnerable to noise-induced hearing loss than when unmedicated.

For this reason, it is recommended to avoid moderate-to-high decibel noise exposures (e.g. sporting events, power tools, chainsaws, concerts, etc.).

If noise exposure is unavoidable – wear properly-fitted (NR30+) earplugs or earmuffs. (I recommend something like these Peltor Earmuffs).

(Disclosure: This is an affiliate link – price is the exact same regardless of whether you buy through my link.)

Regular audiological exams

Audiometric examinations should be attained before azithromycin treatment (if possible) then at various intervals throughout treatment.

Audiometric examinations may be able to detect early hearing loss (e.g. high frequency) before noticed by the patient.

Early detection will ensure that treatment is stopped before hearing loss progresses and/or becomes irreversible.

Otoprotective supplements

Various otoprotective supplements may help prevent or azithromycin hearing loss – or reduce its magnitude and post-onset rate of progression.

Discuss otoprotective supplements with a medical doctor to ensure that they are safe to take based on your current medication regimen and medical status.

If safe, it is recommended to use otoprotective agents throughout azithromycin therapy.

Nutrient-dense diet

Consuming a nutrient-dense diet should help provide adequate vitamins/minerals – some of which may be otoprotective (via antioxidant/anti-inflammatory effects).

Deficiencies in vitamins/minerals could increase azithromycin-related hearing loss.

Avoid or reduce stress

Stress can decrease blood flow to extremities via vasoconstriction (possibly within the inner ear), create vitamin/mineral imbalances, and increase inflammation – all of which could synergistically increase vulnerability to azithromycin-induced hearing loss.

For this reason, it is recommended to avoid/reduce stressors and manage stress if levels are high.

Get enough quality sleep

Getting adequate quality sleep helps the body repair itself following insult.

Sufficient sleep will keep the body’s endogenous antioxidant response system functioning properly – and should help reduce inflammation.

Poor sleep on the other hand can increase inflammation and stress – whereby vulnerability to azithromycin-related hearing loss could increase.

Stay hydrated

Dehydration is associated with altered pharmacokinetics of medications – including: decreased distribution, slower clearance, and prolonged half-life.

Adequate hydration will ensure proper distribution of, and normal clearance rate of, azithromycin – thereby decreasing risk of ototoxicity and hearing loss.

Avoid smoke exposure

Though it’s unclear as to whether smoke exposure directly causes hearing loss – many suspect that it could (such as by reducing cellular oxygenation, increasing inflammation, and increasing oxidative stress).

Because smoke exposure may increase vulnerability to azithromycin-related hearing loss – it is recommended to avoid smoke during treatment.

Note: There may be additional ways to prevent, reduce likelihood of, or (should it occur) decrease magnitude of azithromycin-related hearing loss. This list is by no means conclusive.

Supplements for azithromycin ototoxicity & hearing loss (Prevention)

Included below are supplements that might be otoprotective during treatment with azithromycin.

Links to these supplements are “affiliate links” – meaning I earn a small commission if you purchase through my links (the cost is the same and it helps support my content creation).

Disclaimer: The otoprotective efficacies of these supplements are relatively unconfirmed in humans – and may vary among individuals.

Always consult a medical doctor before using any supplement(s) to ensure that they are safe with your current medication(s) and medical status.

- Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E + Magnesium: The simultaneous administration of vitamins A, C, E + magnesium has been shown to elicit otoprotective effects. (R) Be cautious about taking too much vitamin A + vitamin E (as these are fat soluble and can accumulate to toxic amounts if not used appropriately).

- Multivitamin: Deficiencies in vitamins/minerals may increase vulnerability to azithromycin-induced hearing loss. For this reason, you may want to use a multivitamin/multimineral supplement.

- NAC (N-Acetyl-Cysteine): NAC is a precursor to glutathione – a master antioxidant within the human body. NAC supplementation tends to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation – each of which could protect against hearing loss. (R) (Ask doctor for a prescription if not available OTC – should be cheap).

- Magnesium citrate, magnesium threonate, magnesium glycinate: Magnesium as a standalone agent may protect against hearing loss via: (1) blocking excessive calcium release; (2) limiting cell energy depletion; (3) inducing vasodilation of arterioles; (4) preventing hypoxia; (5) normalizing mitochondrial membrane function; (6) inhibition or scavenging of free radicals; and/or (7) counteracting glutamate excitotoxicity. (R)

- Vitamin D: Deficiencies in vitamin D may cause and/or increase susceptibility to cochlear deafness. For this reason, it is recommended to supplement with vitamin D if you are deficient (e.g. fail to get adequate UVB sunlight). (R)

- Glutathione: Research models indicate that glutathione may be capable of preventing and/or reversing various forms of hearing loss. Though supplementation with NAC will increase glutathione levels – some people may get better results with glutathione itself. (R)

- Alpha lipoic acid: Studies show that alpha-lipoic acid can protect against cisplatin-induced hearing loss in animal models. Alpha-lipoic acid seems to decrease apoptotic cell death in both inner and outer hair cells via reducing inflammation, decreasing intracellular reactive oxygen species, modulating gene expression, normalizing mitochondrial function, and preventing depletion of glutathione in the cochlea. (R)

- Ubiquinol: Studies suggest that the administration of ubiquinol (a reduced form of CoQ10) or CoQ10 (ubiquinone) may prevent sensorineural hearing loss. In rats, CoQ10 plus a multivitamin protected against cisplatin ototoxicity – and a trial in humans revealed that CoQ10 with corticosteroids may promote hearing recovery in persons with sudden sensorineural hearing loss. (R)

- Vitamin C: Evidence suggests that high-dose intravenous vitamin C (HDVC) may help reverse idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss when combined with corticosteroids. High doses of vitamin C decrease reactive oxygen metabolites produced by inner ear ischemia or inflammation. Vitamin C is also synergistic with vitamins A & E – plus magnesium in protecting the ears. (R)

- D-Methionine: Methionine is an essential amino acid found in cheese and eggs. Studies suggest that supplementation with D-methionine protects against hearing loss via increasing mitochondrial glutathione and antioxidant status. (Only found L-methionine as a supplement – may not have the same effect as the D-isomer).

- Taurine: Taurine is a sulfur-containing amino acid that’s widely distributed throughout animal tissues. Preliminary data indicate that taurine reduces ototoxicity of aminoglycoside antibiotics via inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in the cochlea. (R)

- Calcium-d-glucarate: While this supplement might not directly protect the ears from hearing loss – it might yield indirect protection via promotion of healthy kidney and/or liver function. Healthy kidney and liver function will minimize the likelihood that azithromycin (and other medications) reach ototoxic levels.

- Krill oil: This is a highly-bioavailable source of omega-3 fatty acids (DHA/EPA). Preliminary data indicate that omega-3 fatty acids may protect against certain types of hearing loss. (R)

- Hydrogen (?): Animal models suggest that hydrogen administration (water or inhalation) protects against medication-induced (cisplatin) ototoxicity and noise-induced hearing loss. Hydrogen administration acts as a therapeutic and preventive antioxidant by specifically reducing hydroxyl radicals (the most cytotoxic of ROS). (R1, R2)

My supplement stack to prevent azithromycin ototoxicity

Included below is my supplement stack that I take in hopes of preventing ototoxicity and hearing loss from my medications (azithromycin, ethambutol, rifampicin).

Keep in mind that these supplements are considered safe for me by my doctors based on my medication regimen and medical status/history – don’t automatically assume they’re safe for you.

I administer these supplements in 2 stacks: (A) morning with breakfast (2+ hours after medications are administered) & (B) evening with dinner.

NAC (N-acetyl-cysteine)

For the first 6 months of my treatment, I’d been administering 600 mg NAC in the morning – then 600 mg NAC in the evening.

Neil Bauman (PhD) convinced me that 1200 mg NAC wasn’t enough for otoprotection – and recommended 2000-2500 mg per day.

(I’ve since upped the dose to 1200 mg in the morning and 1200 mg in the evening).

Note: No longer available OTC for “regulatory” reasons. However, most people should be able to convince a doctor to get a prescription.

If unable to get NAC (for whatever reason) you may want to consider Glutathione.

Alpha Lipoic Acid

I take 250 mg alpha-lipoic acid in the morning – and another 250 mg alpha-lipoic acid in the evening to scavenge free radicals and support glutathione production.

Multivitamin

I take 1 basic multivitamin/multimineral supplement in the morning with fatty foods to enhance absorption.

This supplement is taken to ensure that I’m covering all my bases and have no glaring deficiencies in vitamins/minerals that might increase susceptibility to medication-related hearing loss.

Magnesium citrate

I take 200-400 mg magnesium citrate in the morning with my: (1) multivitamin (containing vitamins A, C, E); (2) vitamin C supplement; and (3) various foods high in vitamins A, C, and E (carrots, apples & bananas, and almonds).

I take an additional 200-400 mg magnesium citrate in the evening before bed.

Some may find that magnesium citrate causes upset stomach, diarrhea, etc.

I found that these effects subsided within ~2 weeks of high-dose/chronic use.

However, if you cannot tolerate magnesium citrate – magnesium glycinate should suffice.

Magnesium glycinate

Not as cost-effective as magnesium citrate, but easier to tolerate for many who experience stomach cramps and/or a pro-diarrheal effect resulting from magnesium citrate.

Subjectively seems to work just as well as magnesium citrate.

Magnesium threonate

Occasionally I’ll take 2000 mg magnesium-l-threonate in the evening along with magnesium citrate.

I usually reduce the dosage of the citrate slightly when adding in threonate.

Vitamin C (acidic) or Vitamin C (non-acidic)

I take 1000 mg vitamin C in the morning with my: (1) multivitamin; (2) magnesium citrate; and (3) foods high in vitamins A, C, and E.

Later I take 1000 mg vitamin C in the evening. For a while I was taking ~2000 mg vitamin C in the AM & another ~2000 mg vitamin C in the PM.

I use the ascorbic acid format, but if you have severe acid reflux – this is NOT recommended.

Individuals with reflux should use non-acidic Calcium Ascorbate. Despite the name containing “clacium” – it’s far more Vitamin C than Calcium.

Vitamin D3

If unable to get vitamin D from the sun (i.e. sufficient UVB exposure), I supplement with vitamin D3 (2000 IU) with or without K2 (90 mcg) in the morning.

Current evidence suggests that D3 is fine without K2 – but some people prefer to take K2 as part of a combination.

Ubiquinol

I prefer ubiquinol over CoQ10 because ubiquinol is CoQ10 in bioactive, antioxidant form.

In adulthood, one’s ability to convert CoQ10 to ubiquinol decreases – so it makes sense to supplement with ubiquinol (as opposed to CoQ10).

I take 100 mg ubiquinol with fatty foods in the morning.

Taurine

I take 1000 mg taurine at dinner with my other evening supplements (vitamin C, magnesium, alpha-lipoic acid, and NAC).

Calcium-d-glucarate

I take 500 mg calcium-d-glucarate with my dinner to promote normal hepatic and renal function while on my medications.

Almonds

Though I don’t consider almonds a supplement, I consume ½ cup almonds every morning for vitamin E.

The almonds are consumed with: carrots, fruits (vitamin C), and magnesium to ensure that I’m getting a combination of A, C, E + Mg.

Occasionally I’ll consume almond milk throughout the day for extra vitamin E.

Be careful about supplementing with Vitamin E though – as it can accumulate in the body and cause toxicity.

Note: My multivitamin also contains vitamin E.

Carrots

Though I don’t consider carrots a supplement, I consume at least 3.25 oz of carrots every morning for the beta-carotene which converts to vitamin A.

The carrots are consumed with: almonds (vitamin E), fruits (vitamin C), and magnesium to ensure the combination of A, C, E + Mg.

Beef liver could be substituted for carrots in persons who inefficiently convert beta-carotene to vitamin A (due to genetics).

Note: My multivitamin also contains vitamin A.

Morning stack: NAC (1200 mg); alpha-lipoic acid (250 mg); multivitamin (1); magnesium citrate (200-400 mg); vitamin C (1000 mg); ubiquinol (100 mg); vitamin D3 & K2 (2000 IU/90 mcg); carrots (3+ oz for vitamin A); almonds (1/2 cup minimum for vitamin E); fruits (for vitamin C)

Evening stack: NAC (1200 mg); alpha-lipoic acid (250 mg); magnesium citrate (400 mg) and/or magnesium-l-threonate (2000 mg); vitamin C (1000 mg); taurine (1000 mg); calcium-d-glucarate (500 mg)

What else I do while taking azithromycin to reduce odds of hearing loss…

- NR30+ Earmuffs: I wear NR30+ earmuffs whenever exposed to moderate or high decibel sound. Why? Because medications like azithromycin might lower decibel thresholds for induction of noise-related hearing loss. (Earplugs are an alternative, but I avoid them because they can cause wax impaction).

- Nutrient-dense, hypercaloric diet: I try to consume a nutrient-dense, hypercaloric diet while on these medications. Why? Because the body might utilize vitamins/minerals from food more effectively than those provided by supplements. Additionally, I eat extra calories to ensure that my weight won’t drop – as I suspect a low bodyweight relative to azithromycin dose might increase risk of hearing loss.

- Enough quality sleep: Getting adequate quality sleep can decrease stress and inflammation – each of which may be otoprotective. Lack of sleep can have the opposite effect (increased stress and inflammation). I aim for around 7.5 to 8.5 hours of quality sleep each night.

- Relaxation & stress avoidance: I try to engage in relaxing activities on a regular basis and avoid stressors. Stress exposure may increase susceptibility to hearing loss as a result of increasing inflammation and reducing blood supply throughout ear structures.

- Exercise (not too much): The optimal amount of exercise can reduce stress and may enhance blood flow to the inner ears for repair. I exercise every day or two with ~20-30 minutes of cardio. I avoid over-exercising, as this could induce inflammation, increase stress hormones, and cause kidney dysfunction (via rhabdomyolysis).

- Stay hydrated: I drink plenty of water throughout the day to ensure that (1) my kidneys clear azithromycin at a normal rate and (2) medications/supplements won’t get stuck in my esophagus.

Note: I’m unsure as to whether these supplements and strategies will actually protect my ears from the potential toxicities of azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampicin – over my 18-month treatment. Nevertheless, I’m doing everything I can to decrease odds of ototoxic reactions.

My experience thus far with azithromycin

Thus far, I’ve been taking azithromycin for around 8 months.

I initiated azithromycin in October 2018 and was initially instructed to take 500 mg per day.

In the second week of treatment I added in rifampicin (600 mg). In the third week of treatment I added in ethambutol (1200 mg).

All medications are taken first thing in the morning simultaneously on an empty stomach with ~1 glass of water.

(Experts recommend avoiding large intakes of water – as this could interfere with absorption and serum concentrations of the medications).

After 3-4 weeks of treatment, my infectious disease doctor recommended that I transition from daily treatment to a Monday, Wednesday, Friday (M, W, F) protocol.

- First day: On the first day of azithromycin treatment, I noticed some ear fullness, ear pain, and discomfort. (It actually felt quite uncomfortable – like the azithromycin was causing a mild ear infection). Two days into treatment I consulted an audiologist for a comprehensive examination – which revealed perfect (better-than-average) hearing.

- First few weeks: During the first few weeks of azithromycin treatment (500 mg/d), I experienced decreased sensitivity to various sounds – but nothing significant.

- 1 to 8 months: From the first through the eighth month of treatment (on the M, W, F regimen) I haven’t experienced any noticeable changes in hearing. Occasionally I’ll experience a faint (nearly undetectable) hum – but I only notice it when wearing my NR30+ earmuffs, so it might be some kind of echo chamber-type effect.

Note: I’ve completed 8/18 months of my treatment. If I remember, I’ll update this article with my hearing status over the next 10 months. I plan on receiving 1-2 more audiological examinations before the end of treatment to detect any subclinical hearing changes.

Update: Completed full ~18 months of treatment and thankfully had zero significant ototoxic reaction to azithromycin.

Mechanisms of Azithromycin Ototoxicity

Included below are hypothesized mechanisms by which azithromycin might induce ototoxicity, hearing loss, and/or tinnitus.

Reducing oxidative phosphorylation capacity (R)

- A paper by Ress and Gross suggests that azithromycin (and other macrolide antibiotics) might cause ototoxicity by reducing oxidative phosphorylation capacity.

- Reduced oxidative phosphorylation is thought to create significant ion imbalances within the cochlea.

- Resulting ion imbalances could trigger cellular damage of the stria vascularis and outer hair cells to cause hearing loss and/or tinnitus.

Mitochondrial dysfunction (R1, R2)

- It is understood that intracellular azithromycin concentrations reach significantly higher levels than plasma or serum concentrations.

- Some researchers suspect that elevated intracellular concentrations of azithromycin may induce mitochondrial dysfunction, which in turn, might lead to ototoxicity.

- An accumulation of mitochondrial DNA damage would lead to increases in reactive oxygen species and decreased antioxidant capacity.

- The combination of mitochondrial DNA damage, elevated reactive oxygen species, and decreased antioxidant capacity, could damage: hair cells of the organ of Corti, stria vascularis, afferent spinal ganglion neurons, and central auditory pathways – resulting in hearing loss and/or tinnitus.

Note: If you know of any additional mechanisms by which azithromycin might induce ototoxicity, feel free to share in the comments section (with relevant scientific sources).

Azithromycin & Hearing Loss (Research)

Included below are synopses of studies in which rates of hearing loss associated with azithromycin were examined and discussed.

Azithromycin and Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Adults: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Authors: Alrwisan et al. (2018) (R)

- Aim: Evaluate whether short-term azithromycin treatment increases risk of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL).

- Methods: Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from Medicaid claims (1999-2010) from adult patients (18-64 years of age) who used azithromycin or amoxicillin ± clavulanate to treat uncomplicated infections. Rates of sensorineural hearing loss among 493,774 patients were calculated (246,887 azithromycin users & 246,887 amoxicillin ± clavulanate users).

- Results: In unmatched cohorts, 392 azithromycin users & 759 amoxicillin ± clavulanate users experienced sensorineural hearing loss. In matched cohorts, 287 azithromycin users & 307 amoxicillin ± clavulanate users experienced sensorineural hearing loss. Unadjusted incidence rates of sensorineural hearing loss were: 38 cases per 10,000 patient-years (azithromycin) and 41 cases per 10,000 patient-years (amoxicillin ± clavulanate).

- Limitations: No audiometric examinations to determine whether hearing ability changed post-treatment from baseline.

- Conclusion: Short-term use of azithromycin is not associated with increased risk of sensorineural hearing loss relative to amoxicillin ± clavulanate. Neither medication is likely to cause sensorineural hearing loss over the short-term.

Macrolide-associated sensorineural hearing loss: A systematic review

- Authors: Ikeda et al. (2018) (R)

- Aims: Investigate the association between macrolide antibiotics and sensorineural hearing loss. Determine specific agents and/or dosages that may induce sensorineural hearing loss – and assess whether interventions exist to reverse macrolide-induced hearing loss.

- Methods: Researchers gathered data from all human studies/reports in which macrolide therapy was associated with sensorineural hearing loss. Next, they extracted data from these studies/reports, including details of (1) treatment regimen and (2) sensorineural hearing loss.

- Results: 44 publications met inclusion criteria for the systematic review (41 retrospective & 3 prospective reports).

- 78 cases of sensorineural hearing loss (as confirmed by audiometric examination) were reported among macrolide users. In these cases, sensorineural hearing loss occurred: (1) with both oral and intravenous administration – and (2) at standard and elevated doses.

- Sensorineural hearing loss was irreversible in 6/78 (7.69%) cases despite macrolide discontinuation and timely corticosteroid treatment. Irreversible sensorineural hearing loss was observed after just 2-3 days of macrolide use.

- Sensorineural hearing loss was reversible in 70/78 (89.7%) cases with standalone macrolide cessation.

- Sensorineural hearing loss was reversible in an additional 2/78 (2.56%) cases with macrolide cessation plus prompt corticosteroid treatment.

- Reversible cases of sensorineural hearing loss generally improved within hours or days.

- 9 studies documented 42 additional cases of subjective (patient-reported) hearing loss among macrolide users – but these were not included in the analysis.

- Oral azithromycin (subgroup): Oral azithromycin was associated with sensorineural hearing loss in 8 retrospective studies (41 patients); 2 prospective studies (12 patients); a retrospective case series (5 patients); and 4 case reports (4 patients). Included below are characteristics of azithromycin-related hearing loss.

- Rapid onset & delayed onset. Hearing loss from azithromycin was occasionally rapid-onset – occurring within the first few days of treatment. In other cases, hearing loss from azithromycin exhibited delayed-onset – occurring weeks or months into treatment.

- Usually reversible. In 12/15 (80%) cases discussed, hearing loss from azithromycin was reversible following its cessation. Treatment with corticosteroids (and occasionally antivirals) helped restore hearing in a subset of these cases.

- Sometimes irreversible. In 3/15 (20%) cases discussed, hearing loss from azithromycin was irreversible despite prompt discontinuation and corticosteroid administration.

- Moderate-to-severe. Magnitude of hearing loss was usually moderate-to-severe (20+ dB) – but was occasionally “mild-to-moderate” and “profound.”

- High frequencies. Azithromycin-related hearing loss typically affected high frequency sounds (50-100 Hz).

- Limitations: Researchers acknowledged limitations of this study, including: study design; medical comorbidities; and concurrent medication use. (In other words, hearing losses could’ve been triggered by medical conditions and/or other medications besides macrolides).

- Conclusion: Ikeda et al. concluded that sensorineural hearing loss may follow azithromycin treatment – regardless of dosage.

Risk of sensorineural hearing loss with macrolide antibiotics: A nested case-control study

- Authors: Etminan et al. (2017) (R)

- Aim: Examine the association between macrolide antibiotic use and sensorineural hearing loss.

- Methods: Gather health claims from patients ages 15 to 60 (between 2006 and 2014) and identify health claims in which sensorineural hearing loss was documented. Among the cases of sensorineural hearing loss, assess usage of macrolide antibiotics relative to amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones (controlling for infection) and albuterol (not associated with hearing loss).

- Results: 5,989 cases of sensorineural hearing loss were identified from a group of 6,110,723 patients. Rates of hearing loss did not differ significantly between macrolide users and users of other antibiotics (amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones).

- Conclusion: Researchers concluded that while macrolide use was significantly associated with sensorineural hearing loss, macrolides are unlikely the cause of this hearing loss based on the fact that hearing loss rates didn’t differ from those of amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones (non-ototoxic medications).

What else warrants consideration?

The ototoxicity of many antibiotics, including amoxicillin and/or fluoroquinolones, may be underreported in the medical literature.

Researchers acknowledged that macrolide use was significantly associated with sensorineural hearing loss, but dismissed the idea that macrolides cause hearing loss based on the fact that amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones (allegedly non-ototoxic medications) were associated with similar rates of hearing loss.

The possibility that all antibiotics analyzed (macrolides, amoxicillin, and fluoroquinolones) exhibit ototoxic potential warrants discussion.

Meta-analysis of the adverse effects of long-term azithromycin use in patients with chronic lung diseases

- Authors: Li et al. (2014) (R)

- Aim: To determine rates of adverse effects associated with long-term azithromycin treatment in patients with chronic lung diseases.

- Methods: Gather data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) – published from 1996 to 2013 – involving patients with chronic lung diseases who received long-term azithromycin treatment. Compare rates of adverse reactions among azithromycin users relative to placebo recipients.

- Results: Long-term azithromycin treatment was associated with increased risk of hearing impairment compared to placebo groups. A total of 148/895 azithromycin recipients (16.5%) experienced hearing impairment – relative to 116/866 (13.3%) of placebo recipients. Older age, daily azithromycin use, and longest treatment durations were associated with greater hearing impairment.

- Limitations: Li. et al. acknowledged limitations associated with this meta-analysis, including: (1) the small number of trials from which data were compiled (only 6 RCTs); (2) potential publication bias (positive results are more likely to get published); (3) potential increase of Type 1 error following calculations.

- Conclusion: Long-term azithromycin treatment may increase risk of hearing impairment – as evidenced by a trend toward hearing impairment after receiving long-term azithromycin therapy. Although a trend for greater hearing impairment among azithromycin users was documented relative to placebo users – it wasn’t of statistical significance.

What else warrants consideration?

Authors aptly highlighted various limitations associated with this meta-analysis including: limited dataset (6 RCTs) and possible publication bias.

- Audiometric examinations (?): It was not mentioned as to whether participants in these RCTs received audiometric examinations at baseline and post-treatment. (I’m assuming they didn’t). For this reason, it’s difficult to know whether (1) azithromycin damaged hearing and (2) the magnitude of damage (if damage occurred). (Many patients won’t report hearing loss or may not fully notice hearing loss if only high frequencies are affected).

- Kidney function tests (?): It was not mentioned whether participants in the RCTs received routine kidney function tests. (I’m assuming they didn’t). Kidney dysfunction can increase max concentrations of azithromycin for prolonged periods and prevent efficient elimination – whereby it could become toxic. (It would’ve been useful to know whether patients with hearing loss exhibited renal dysfunction).

- Dosing, frequency, duration of administration: There were differences between many of the trials in azithromycin dosing (250 mg vs. 500 mg; bodyweight-based dosing vs. fixed dosing), frequency of use (daily vs. 3 days per week), and total duration of administration (26 weeks, 168 days, 6 months, 1 year). Data suggest that daily dosing for longer-terms (1-year) may increase risk of hearing loss (irrespective of dose).

- Patient-specific variables: Data suggest that older-aged patients may be at greater risk of hearing loss associated with azithromycin – than younger patients. Other patient-specific variables that were not tracked, but may have increased risk of azithromycin-related hearing impairment, include: comorbid medical conditions, concurrent medication use, nutrition, sleep quality/quantity, and stress level.

Reversible ototoxic effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin on transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions in guinea pigs

- Authors: Uzun et al. (2001) (R)

- Aim: Evaluate the ototoxic potential of azithromycin and erythromycin (macrolide antibiotics) in guinea pigs by measuring transiently-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE).

- Methods: Administer single doses of erythromycin (125 mg/kg, IV), azithromycin (45 mg/kg, orally), and clarithromycin (75 mg/kg, IV) – and measure changes in transiently-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE).

- Results: Azithromycin (45 mg/kg, orally) and clarithromycin (75 mg/kg, IV) reversibly decreased the transiently-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE) – whereas erythromycin had no significant effect. Reversible reductions in transiently-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE) associated with azithromycin and clarithromycin fits the clinical picture of macrolide ototoxicity.

- Conclusion: This study supports the idea that azithromycin could be ototoxic to humans via inducing transient dysfunction of outer hair cells within the ear.

- Limitations:

- Ototoxic potential. The ototoxic potential of azithromycin might differ between guinea pigs and humans. Perhaps guinea pigs are more susceptible to azithromycin ototoxicity than humans.

- Mechanism(s) of ototoxicity. The mechanism(s) by which azithromycin is ototoxic might differ between humans and guinea pigs.

- Pharmacokinetics. Differences in azithromycin pharmacokinetics between humans and guinea pigs might yield different rates of ototoxicity between species.

- Relative doses of azithromycin. The doses of azithromycin administered to guinea pigs in this study were equivalent to 1500 mg human doses – nearly 3-fold more potent than a standard adult dose (500 mg). The dose might determine whether ototoxicity occurs.

Azithromycin Ototoxicity (Case Reports)

Included below are case reports in which patients using azithromycin experienced hearing loss.

Sensorineural hearing loss after chronic azithromycin use

- Authors: Kim et al. (2016) (R)

- Case report: 33-year-old male presented with 1.5 weeks of sudden bilateral hearing loss after taking azithromycin (600 mg/d) for the previous 33 months to treat disseminated MAC and tenofovir for AIDS.

- Details: Hearing loss was symmetric and non-progressive. Patient specifically reported difficulty understanding speech and low frequencies. Otoscope exam and Rinne & Weber tests were normal, finger rub hearing was intact, brain scans (CT & MRI) were normal. Audiometric examination revealed bilateral, moderately-severe sensorineural hearing loss.

- Comorbidities: AIDS (acquired-immune deficiency syndrome); disseminated MAC (mycobacterium avium complex); cachexia (physical wasting); renal tubular acidosis with acute kidney injury (AKI); hypothyroidism

- Interventions: Azithromycin was discontinued due to concerns of ototoxicity. Tenofovir was replaced with zidovudine and lamivudine due to nephrotoxicity.

- Outcome: 7 weeks post-discharge, the patient [subjectively] reported that his hearing had returned to baseline. (This self-report was not verified via follow-up audiometric examination).

- Conclusion: Azithromycin likely caused reversible hearing loss in the context of malnutrition-induced acute kidney injury (AKI). Authors state that azithromycin-related sensorineural hearing loss is usually: reversible, bilateral, symmetrical, and affects conversational speech frequencies. Clinicians are encouraged to be aware of this adverse reaction.

Why the hearing loss in this case?

- Renal dysfunction: The patient experienced renal dysfunction (renal tubular acidosis with acute kidney injury) during treatment – likely due to malnourishment and/or tenofovir, a medication known to cause nephrotoxicity. Renal dysfunction is the primary risk factor for azithromycin ototoxicity.

- Azithromycin ototoxicity: Following renal dysfunction, the patient likely experienced ototoxicity due to increases in azithromycin’s: (1) average peak concentrations AND (2) area under the concentration time curve.

- Tenofovir ototoxicity (?): It’s possible that tenofovir, a medication associated with several toxicities, elicited ototoxic effects in the context of renal dysfunction. It’s also possible that tenofovir and azithromycin synergistically induced ototoxicity in this patient due to renal dysfunction and malnutrition.

- Cachexia & low BMI: Cachexia (physical wasting) led the patient to weigh 85.98 lbs. (BMI of 14.9). A high azithromycin dose-to-bodyweight ratio may have increased this patient’s risk of ototoxicity due to the smaller, concentrated area for azithromycin distribution/saturation – especially in the context of renal dysfunction.

- Malnutrition: Medical doctors noted that the patient was malnourished. Though the malnourishment was deemed the primary cause of renal dysfunction, it may have also increased risk of azithromycin ototoxicity due to deficits in otoprotective vitamins/minerals – many of which may help prevent medication-related ototoxicity.

Other possible causes of hearing loss in this patient:

- Infection (?): It’s unlikely that disseminated MAC infection caused this patient’s hearing loss, however, it remains unclear as to whether the MAC infection was responding to treatment. Conventional treatment for MAC involves azithromycin – plus ethambutol and rifampicin (neither of which were reported to have been used by the patient). If the MAC infection wasn’t properly controlled, it could’ve: (1) spread to the inner ear and/or (2) triggered an immune response that affected hearing.

- AIDS (?): The patient was diagnosed with AIDS. Research indicates that HIV/AIDS patients tend to have poorer hearing at lower frequencies than uninfected controls. Perhaps manifestations of AIDS (even if well-managed with medications) contributed to transient hearing loss in the context of malnutrition and/or increased susceptibility to medication ototoxicity.

- Hypothyroidism (?): Hypothyroidism can cause hearing loss in some cases, however, it’s usually a congenital hearing loss as a result of improper cochlear development. For this reason, hypothyroidism likely didn’t cause this patient’s hearing loss.

Reversible hearing impairment: delayed complication of murine typhus or adverse reaction to azithromycin?

- Authors: Lin et al. (2010) (R)

- Case report: A 55-year-old male with headache, fever, and chills was treated with azithromycin (500 mg/daily); cephradine (250 mg/4x daily); and acetaminophen (500 mg/3x daily) for 3 days in the ER before discharge. Five days post-ER discharge, the patient developed sudden bilateral hearing loss and returned to the ER where he was diagnosed with hepatic impairment and murine typhus infection.

- Details: Pure tone audiometric testing revealed bilateral hearing impairment of total frequency.

- Interventions: The patient received prednisolone (30 mg, b.i.d.) in attempt to preserve/restore hearing. The patient also received acyclovir (750 mg/8 h), ceftriaxone (1 g/12 h), and vancomycin (1 g/12 h) for the murine typhus infection.

- Outcome: A subset of the patient’s hearing ability recovered 11 days after ER discharge – but he was left with residual bilateral high-frequency hearing loss. At ~1-year after discharge, audiometric testing follow-up reported no further changes in hearing beyond residual bilateral high-frequency hearing loss.

- Conclusion: Medical experts suspect that murine typhus infection caused hearing loss in the aforementioned patient. However, it was mentioned that azithromycin-induced hearing loss cannot be ruled out. Other variables I’ve highlighted above (and synergistic permutations) might’ve also caused in hearing loss in this patient and/or prevented hearing recovery.

Why the hearing loss in this case?

Unclear. This case of hearing loss is complex in that the patient: (1) had an untreated murine typhus infection; (2) received a cocktail of medications with ototoxic potential (azithromycin, cephradine, acetaminophen); and (3) exhibited impaired liver function.

Authors Lin et al. state that an adverse reaction to azithromycin cannot be ruled out as the cause of this patient’s hearing loss, however, authors suspect that the hearing loss was more likely a complication of murine typhus infection (as opposed to azithromycin ototoxicity).

Why? Because the hearing loss developed 4 days after azithromycin discontinuation (rather than during the azithromycin usage period).

Though authors state that hearing loss from azithromycin is rare – they also acknowledge that hearing loss from murine typhus is rare.

Since azithromycin has a long half-life of 68 hours, it requires around 15.6 days (on average) to fully eliminate from systemic circulation. This means that azithromycin would’ve remained active in the patient’s system following initial discharge from the ER.

Though the concentration of azithromycin would’ve declined after its cessation – it’s possible that (1) the initial 3-day azithromycin administration coupled with (2) lingering effects of azithromycin following its discontinuation caused or contributed to ototoxicity and corresponding hearing loss.

It’s also possible that untreated murine typhus infection is solely or mostly to blame for this patient’s hearing loss.

Why? Research shows that rickettsiae infections (like murine typhus) can trigger a vasculitis that affects that vasa vasorum and vasa nervosum of the cochlea and cochlear nerve, respectively.

Additionally, rickettsiae can: directly invade parts of the inner ear and trigger strong immune responses that damage inner ears/auditory nerves.

Preliminary data indicate that corticosteroids have no effect on rickettsiae infection-related hearing loss – which is consistent with this case.

In fact, authors referenced a case report from 2008 in which sudden bilateral hearing loss occurred in a patient with murine typhus ~3 weeks after symptom onset.

Similar to the 2008 case, hearing loss in this case report was documented as a delayed, post-acute complication of murine typhus.

Furthermore, because: (1) hearing loss from azithromycin is often reversible in long-term users and (2) this patient’s hearing loss wasn’t fully reversible – authors suggest that the hearing loss was less likely caused by azithromycin and more likely caused by murine typhus.

That said, there are known cases of irreversible azithromycin-related hearing loss (even after short-term use).

Lastly, it’s possible that the patient’s hearing would’ve made a greater recovery if he hadn’t been treated with vancomycin and ceftriaxone (both of which can be ototoxic – and may have interfered with hearing recovery and/or solidified the preexisting threshold shift).

Other possibilities (not mentioned by authors) include…

- Hearing loss from azithromycin killing murine typhus. Pathogenic microbes can release toxins following death – which may have damaged the inner ear. The patient may have developed hearing loss as a consequence of killing some murine typhus microbes with azithromycin.

- Acetaminophen. Research suggests that acetaminophen can cause hearing loss. Given that acetaminophen is metabolized by the liver, and the patient exhibited liver impairment, perhaps the acetaminophen contributed to his hearing loss.

- Synergism of variables: It’s possible that there was some sort of synergism between any of the following variables: (1) murine typhus infection; (2) azithromycin; (3) acetaminophen (plus hepatic impairment); (4) immune reactions to murine typhus infection; (5) murine typhus death (and toxin release); (6) cephradine; – that contributed to this patient’s hearing loss.

- Unknown variables: We remain unaware of whether the patient had: (1) been exposed to loud noises; (2) adequate vitamin/mineral levels; (3) normal kidney function; (4) managed stress/gotten adequate sleep; (5) a genetic predisposition to hearing loss. Each of these variables could’ve also played a role in the outcome.

Sensorineural hearing loss as a probable serious adverse drug reaction associated with low-dose oral azithromycin

Authors: Mick & Westerberg (2007) (R)

Case report: A 47-year-old female developed sensorineural hearing loss, abdominal pain, and arthralgia after receiving azithromycin to treat otitis media.

Details: A 6-day course of azithromycin was prescribed (August 2003) to treat otitis media (one week after receiving amoxicillin with no response). Otitis media resolved but sudden hearing loss occurred 7 to 10 days after her first azithromycin dose.

Hearing loss stabilized but was irreversible. Audiogram revealed bilateral, symmetrical, moderate-to-severe sensorineural hearing loss at all frequencies.

Azithromycin ototoxicity was not initially suspected and hearing aids were recommended. In November 2003, the woman developed subsequent ear pain and was prescribed another 6-day course of azithromycin to treat a suspected ear infection.

Following the administration of 750 mg azithromycin (500 mg on day 1 – then 250 mg on day 2), the woman reported experienced hearing loss in her left ear (along with abdominal pain, blurred vision, and arthralgia).

Her symptoms worsened such that, ~3 days after treatment initiation, she reported blindness in her left eye and an inability to hear. Audiogram revealed moderate-to-severe (right ear) and profound (left ear) sensorineural hearing loss.

Hearing ability declined at all frequencies relative to the previous audiogram.

Intervention: Prednisone (a corticosteroid) was prescribed in attempt to preserve/restore hearing.

Outcome: Hearing failed to improve following discontinuation of azithromycin. Audiogram evaluation ~8 months post-treatment revealed no change in hearing ability. (Arthralgia and otalgia resolved within 3 weeks – and visual impairment was determined to be cataracts).

Conclusion: Using the Naranjo probability scale, azithromycin was deemed to be the “probable” cause of this woman’s sensorineural hearing loss. For this reason, physicians should know that hearing loss can occur as an adverse reaction to azithromycin in select patients.

Why the hearing loss in this case?

Azithromycin ototoxicity. The woman presented in this case experienced multiple episodes of hearing loss as a result of azithromycin treatment.

Other reactions such as vision changes, arthralgia, and abdominal pain were thought to be related to azithromycin toxicity.

It is unknown as to why this particular woman was adversely affected by azithromycin treatment.

Variables not mentioned by authors that may have increased odds of adverse reactions to azithromycin for this woman include: renal dysfunction, preexisting medical conditions, dehydration, vitamin/mineral deficits, noise exposure, high stress, poor sleep, and/or genetic predisposition.

2 cases of reversible hearing loss in patients treated with azithromycin.

Authors: Mamikoglu and Mamikoglu (2001) (R)

Case series: 2 patients developed sudden hearing loss during treatment with low-dose azithromycin. In both patients, hearing returned to normal levels.

Case #1: A 54-year-old female with influenza initiated treatment with azithromycin (500 mg/d) for 3 days.

- Details: The patient was not prescribed azithromycin – yet purchased it over-the-counter (as it is not a prescription medication in Turkey) in attempt to treat influenza. Hearing threshold fell to 70 dB (left ear) on the third day of therapy.

- Intervention: Immediately after presentation to medical doctors, the patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroids and antiviral therapy.

- Outcome: Hearing threshold returned to the 30 dB range after 5 days of corticosteroid and antiviral therapy.

Case #2: A 60-year-old female with acute otitis media plus a hypothesized viral upper respiratory tract infection was prescribed a standard 5-day course of azithromycin (500 mg for the first day, then 250 mg for the remaining 4 days).

- Details: The patient returned to the medical office complaining of tinnitus in her infected ear. Physical examination revealed improvement in eardrum appearance with a mild effusion. Audiologic evaluation indicated mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss with an average 10 dB bone gap in the affected ear.

- Outcome: Hearing returned to baseline (i.e. normalized) after completion of azithromycin therapy.

Conclusion: Azithromycin may cause hearing loss in a small percentage of patients.

Authors suspect that viral infection might decrease the susceptibility threshold for developing hearing loss while using azithromycin.

Nonetheless, it seems as though azithromycin-related hearing loss may be reversible following: (1) completion of short-term therapy; (2) immediate discontinuation at tinnitus/hearing loss onset; and/or (3) treatment with corticosteroids and antivirals.

Why the hearing loss in these patients?

Case #1. In the first case, the patient with influenza administered azithromycin without a prescription. It warrants consideration that influenza may have been solely culpable for transient hearing loss in this patient.

Additionally, a viral infection like influenza might lower the threshold for induction of azithromycin ototoxicity. (There may have been a synergistic effect at play).

Case #2. In the second case, the patient with otitis media plus a [hypothesized] viral upper respiratory tract infection likely experienced reversible hearing loss primarily from otitis media.

It’s possible that azithromycin induced mild ototoxicity within the patient’s ear – particularly since the ear’s defenses were lowered from preexisting infection-mediated and/or immune-related inflammation.

It’s also possible that pathogens (responsible for the infection) emitted toxic metabolites during or in the aftermath of azithromycin treatment. These toxic metabolites may have transiently damaged the inner ear, whereafter, innate repair mechanisms restored hearing.

Other possibilities: Other variables that were not mentioned, but may have contributed to the transient hearing losses, include: renal impairment; old age; low body weight; inadequate hydration; vitamin/mineral deficits; high stress & poor sleep; and noise exposure.

Irreversible sensorineural hearing loss as a result of azithromycin ototoxicity. A case report.

- Authors: Ress & Gross (2000) (R)

- Case report: A healthy 39-year-old female presented to a medical clinic with sudden onset bilateral tinnitus and sensorineural hearing loss following initiation of azithromycin monotherapy for the treatment of a urinary tract infection (UTI). The patient experienced no vertigo, balance problems, or other vestibular symptoms.

- Details: Tinnitus emerged within 24 hours of the first dose (500 mg) of a standard 5-day course (500 mg for 1 day – followed by 250 mg for 4 days). Otoscopic examination findings were normal (intact, mobile tympanic membranes). Audiometric testing revealed moderate-to-severe high frequency sensorineural hearing loss (right ear) and mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss (left ear). Speech discrimination was 92% (right ear) and 96% (left ear) at 40 dB above speech reception threshold. Pressure, compliance, and acoustic reflexes were normal.

- Interventions: Azithromycin was discontinued after the second dose due to exacerbation of tinnitus and bilateral hearing loss.

- Outcome: 12 months following azithromycin discontinuation, the patient exhibited slight improvement in hearing – but nothing significant. The patient still complained of bilateral tinnitus – and there were no changes on audiometric findings (relative to initial examination). The patient exhibited residual sensorineural hearing loss in both ears – especially from 2 to 8 kHz – with greater losses at higher frequencies.

- Conclusion: This case differs from most cases of azithromycin ototoxicity in that the sensorineural hearing loss: (1) emerged within 2 days of azithromycin treatment; (2) occurred at standard azithromycin doses; (3) was irreversible; (4) couldn’t be attributed to confounds (e.g. preexisting conditions, medications, etc.). This case highlights the fact that permanent hearing loss can occur from short-term, standard-dose azithromycin treatment.

Why the hearing loss in this case?

Azithromycin ototoxicity. The patient experienced sudden onset bilateral tinnitus within 24 hours of administering a single 500 mg azithromycin dose – and a worsening of tinnitus plus bilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss following administration of a subsequent 250 mg azithromycin dose.

No medical conditions, medical history, or confounding variables were discovered that would’ve increased risk for hearing loss in this patient.

Experts hypothesize that the action of azithromycin on ribosomal subunit binding might decouple oxidative phosphorylation to create ion imbalances in the cochlea – thus causing sensorineural hearing loss in persons with genetic predisposition.

Though the hearing loss was probably caused by azithromycin, it would’ve been helpful to know the patient’s: (1) body weight (as a high dose-to-weight ratio may increase risk of this reaction) (2) renal function (this wasn’t tested, but if slightly impaired, might’ve played a big role in the ototoxicity); (3) body composition (body fat percentage may influence azithromycin tissue distribution).

We also don’t know whether other variables may have contributed to the ototoxicity (perhaps synergistically), including: noise exposure; insufficient hydration (to promote azithromycin clearance); vitamin/mineral deficits; high stress/poor sleep; and/or genetic predisposition to hearing loss.

Additional papers discussing azithromycin-related hearing loss

- Azithromycin-Induced Hearing Loss (1999) (R)

- Azithromycin-Related Hearing Loss In Patients with HIV (1997) (R)

- Ototoxicity with Azithromycin (1994) (R)

Note: If you know of any additional case reports of azithromycin ototoxicity that weren’t mentioned here, be sure to share them in the comments section. (I’ll add links to them here).

Conclusions (re: Azith & HL)

Below are some conclusions I’ve drawn based on my research of azithromycin and hearing loss.

- Azithromycin-related hearing loss is a rare adverse reaction, occurring at an estimated rate of 38 cases per 10,000 patient years, among patients receiving short-course treatment.

- Azithromycin-related hearing loss can affect anyone, regardless of: dose, administration frequency, and treatment duration.

- Patients using high doses of azithromycin, on a daily basis, over a long-term are thought to be at greatest risk of developing azithromycin ototoxicity.

- Other risk factors for azithromycin-related hearing loss include: renal dysfunction, old-age (65+), serious infections, concomitant medication use, malnourishment, and chronic medical conditions (e.g. HIV/AIDS).

- Most cases of hearing loss from azithromycin are reversible wherein hearing: improves (to an extent) or is fully recovered post-loss.

- Select cases of azithromycin-related hearing loss are irreversible wherein hearing fails to improve or worsens post-loss.

- Prompt cessation of azithromycin plus administration of corticosteroids, antivirals, and/or other otoprotective supplements should increase odds of hearing recovery and/or degree of recovery – post-loss.

- Compared to other popular antibiotics (e.g. amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones), data suggest that azithromycin is associated with either statistically similar or lower rates of hearing loss.

The bottom line

Azithromycin is a highly-effective antibiotic with few unbearable side effects and low risk of adverse reactions – especially when administered for a short-term at standard doses (e.g. 5-days at 500 mg on day 1 – then 250 mg days 2 through 5).

In fact, most experts regard azithromycin as being among the safest antibiotics available.

Nonetheless, hearing loss can occur in any azithromycin user – regardless of dosage, age, health, etc.

If hearing loss occurs while using azithromycin, it is recommended to: (1) seek emergency medical care and (2) discontinue the medication (if possible).

Have you experienced hearing loss from azithromycin?

Included below are a list of questions that I’d appreciate you answer if you’ve experienced changes in hearing while taking azithromycin.

Hearing ability

- Did you test your hearing before taking azithromycin with an audiologist?

- If not, how can you be sure that hearing loss is attributable to azithromycin?

- Did you re-test your hearing at various intervals while using (or after using) azithromycin?

- If you experienced hearing loss and/or tinnitus while taking azithromycin, what was the magnitude of the loss? Which specific frequencies were affected?

- Did your hearing recover after azithromycin cessation?

- How long did recovery take?

- What was the degree of recovery? (e.g. 50%, 75%, 100%)

- If you experienced hearing loss and/or tinnitus while taking azithromycin, did doctors prescribe corticosteroids and/or antivirals to increase odds of hearing recovery?

- Did your hearing recover after azithromycin cessation?

Azithromycin use

- For which specific medical condition were you prescribed azithromycin?

- Have you considered that certain conditions for which azithromycin is prescribed (e.g. infections) might induce hearing loss?

- What dosage of azithromycin do you (or did you) take? (e.g. 250 mg/d, 500 mg/d, 600 mg/d)

- How often do you (or did you) administer azithromycin? (e.g. daily, every-other-day, 2x/week, MWF)

- In total, how long have you used azithromycin? (e.g. 5 days, 6 months, 1 year)

- If you experienced hearing impairment while taking azithromycin, did you immediately discontinue treatment and consult a medical doctor for treatment?

Kidney function

- Did you check your kidney function at baseline? (If so, how was it?)

- Did you re-check your kidney function at various intervals while using azithromycin? (If so, how was it?)

Additional details

- What is your age?

- What is your body weight?

- Which medications, supplements, or drugs do you (or did you) use with azithromycin?

- Have you considered that the cumulative effects of azithromycin plus other agents/substances may synergistically trigger hearing loss?

- Do you take any supplements? (If so, which ones?)

- Are any taken specifically in effort to prevent azithromycin ototoxicity?

- Do you consume a nutrient-dense diet?

- Are you exposed to high stress on a regular basis?

- How is your sleep quality/quantity?

- Were you exposed to any loud noise(s) during azithromycin treatment? (e.g. concerts, chainsaws, jet engines, lawnmowers, airpods, etc.) – If so, have you considered that your hearing loss may be noise-induced?

- Do you have any comorbid medical conditions that could cause hearing loss?

- Do you have a family history of/genetic predisposition to hearing loss?

- Do you have any risk factors for azithromycin ototoxicity?