Why did the “War on Drugs” fail massively in the United States?

In my opinion, the “War on Drugs” massively failed in the U.S. because the U.S. was never serious about winning it.

If the U.S. were serious about actually winning a war on drugs, it would:

- Invest money and resources in drug use/abuse prevention and education

- Rehab programs

- Drug policing

- Impose harsher penalties for drug possession, distribution, administration

Why hasn’t the U.S. tried to win the war on drugs?

Because the U.S., as a whole, is too conflicted on drug policy (i.e. there’s no general consensus) – thought around this subject is far too diverse.

This becomes blatantly obvious when we analyze the discrepancies between various states in:

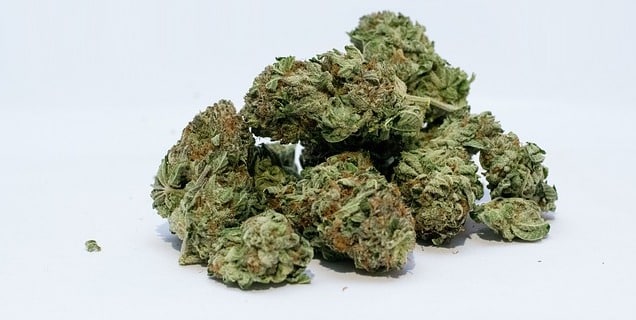

- Drug legality (e.g. cannabis legality; kratom legality; et al.)

- Drug laws (e.g. sentencing is harsher in certain states than others for possession, trafficking, usage, etc.)

Are any countries actually winning the War on Drugs? (Strategies)

Yes. Singapore seems to be doing a good job – and is clearly winning the “war on drugs.”

1. Investment in prevention & education

The Singaporean government works closely with community groups, parents, and teachers to educate Singaporean youth and the general public on potential harms and serious consequences of drug abuse. (R)

In 2008, the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) outlined Preventive Drug Education strategies used in Singapore (via a PDF-type slide-show presentation). (R)

The goal of the CNB is: “a Singapore without drugs – where everyone can live, work, and play safely.”

Harm prevention strategy

Singapore uses a combination of (1) targeted prevention, (2) strong deterrence, (3) upstream intervention for young abusers, and (4) rehabilitation/supervision to reduce relapse rates.

(This requires a combination of familial and community engagement plus enhancing systems and structures).

Universal prevention

- Compulsory education: Youths between 6 and 15 are required to receive drug education.

- Character and Citizenship Education (Life Skills): Build resilience against adversities (so people are less likely to turn to “drugs” when times get tough).

- Universal preventive education: Educate youth about risks of drug-taking between primary and tertiary education. (Inoculation theory).

Developmental phase (age) vs. drug prevention strategy

Singapore implements an age-related education/prevention strategy in accordance with cognitive abilities of persons in the specific age group.

Age 7-12: Educate and inoculate via family and educators. Keep things as simple as possible and discuss physical harm and legal consequences. Why? Cognitive abilities are low and “concrete thinking” is most likely.

- Takeaway: “Drugs are harmful.”

Kids aged 10-11 are given Anti-Drug Ambassador Activity (AAA) booklets with cartoon-like characters to help kids understand that drugs are harmful.

There are competitions held by schools for the “best anti-drug montage” exhibition at the end of activity period.

Age 13-16: Reasoning via parents and mass media. Curiosity about drugs is “moderate-to-high” and “analytical thinking” is emerging. Showcase consequences of taking different drugs (e.g. physical harm, legal consequences, social consequences).

- Takeaway: “Drug abuse has lifelong impact and it is a matter of time before abusers get addicted and arrested.”

Age 17-25: Inculcate appreciation of Singapore’s drug policy. Curiosity about drugs is “moderate-to-very high” at this age. Use “systems thinking” to showcase why Singapore’s tough stance on drugs is necessary and highlight the long-term harms of drug use to youth culture and society.

- Takeaway: “Drug abuse will undermine youth and degrade society.”

Additional protective strategies

Annual stakeholder meetings: Schools, Voluntary Welfare Organizations, Self-Help Groups, and relevant Government Agencies – have annual meetings to review/revise strategies for keeping drug abuse/use low.

Ministry of Education (MOE): Encourages students to take part in at least 1 CCA (e.g. chess club, physical sport, performing art, uniformed group) to devote time to meaningful activities.

Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association (SANA): Organizes a badge scheme for uniformed group CCAs to raise anti-drug awareness in schools.

The following all have programs to discourage drug use: Ministry of Social and Family Development; Ministry of Education; Ministry of Health; Ministry of Home Affairs; State Courts; Academics; Self-Help Groups.

National Youth Perception Survey: This helps Singapore to gauge general perceptions of drugs (to some extent) among persons who have moderate-to-very high curiosity about them.

Each year Singapore administers a “youth perception survey” via the National Council Against Drug Abuse (NCADA).

A sample of Singaporeans between ages 13 and 30 fill out a survey to measure perceptions and attitudes toward drug taking.

This includes 24 pairs of in-depth interviews (IDIs) with youth.

Social media campaigns: Singapore runs various “anti-drug” campaigns to discourage youth from trying drugs. These campaigns include professional musicians and sports players who showcase successes of a drug-free lifestyle.

Community & Youth Advocacy: United Against Drugs Coalition: The UADC is an anti-drug alliance that rallies support from local organizations to raise awareness of drug abuse in society via outreach programs.

Anti-Drug Abuse Advocacy (A3) Network: The AAA unites passionate individuals from different walks of life to educate and empower them to advocate for a drug-free Singapore.

Youth advocacy program: A youth program features various young Singaporeans that discuss and advertise the damages that drugs do to communities.

Note: I’m not sure of the monetary amount invested in drug abuse prevention and education in Singapore (couldn’t find any data online). Additionally, I’m not sure how the strategies employed in Singapore compare to other countries (e.g. U.S.A.).

From everything I’ve read, it seems as though Singapore has a nuanced and targeted strategy (relative to age) for preventing drug use… (I’m guessing it’s a bit more targeted than the U.S. – but could be wrong).

Moreover, there are clearly an abundance of organizations (e.g. health, self-help, volunteer, educational, etc.) focused on minimizing drug use in at-risk populations youth, teens, and young adults.

Although this is a total guess, I suspect that Singapore invests significantly more in both: (1) money and (2) efforts – per capita – relative to the U.S. (and most countries) in drug use prevention.

According to SAMHSA, if effective drug prevention programs were implemented nationwide, substance abuse initiation would decline for ~1.5M youth and be delayed ~2 years. (R)

In 2003, this would’ve led to an estimated:

- 8% fewer youth binge drinking

- 5% fewer youth using cannabis

- 8% fewer youth using cocaine

- 7% fewer youth smoking regularly

SAMHSA’s cost-benefit analysis concluded: “the benefits of substance abuse prevention outweigh the costs of providing that service.”

2. Drug rehabilitation programs

In Singapore, drug abusers are put into mandatory rehab programs to help them “kick” existing addictions/habits.

Upon completion of drug rehab, ex-users receive assistance (e.g. counseling with accountability via check-ups) to reintegrate into society.

In other words, if you’re a drug abuser, the government requires that you complete rehab – and supports/monitors your reintegration into society (such as by: check-ups to ensure that you stay clean, helping you find and maintain a job, etc.).

It remains somewhat unclear as to whether drug rehabilitation programs in Singapore are government-subsidized. I’m guessing that as long as it’s not some ultra-fancy “private” rehab clinic – it’s government subsidized to an extent.

Why? Singaporean citizens and permanent residents are entitled to subsidized healthcare services (subsidies range from 50-80%). (R)

How does this compare to the U.S.? In the U.S., the government cannot force someone into rehab.

In 37 states and D.C., medical professionals and families can petition to have a drug abuser forced into rehabilitation. (R)

That said, it’s unknown as to what percentage of professionals and families actually do this – and how it’s done.

In many cases, I’d guess that drug abusers avoid medical doctors (due to lack of insurance) and may not interact with their families (such that families would know their phone, address, etc.) – which significantly reduces odds of “forced rehab.”

Are there public or state-funded rehab facilities in the U.S.? Yes.

However, these generally require people to have at least some form of insurance.

Many drug abusers do not bother signing up for insurance and thus cannot afford out-of-pocket expenses even for state-funded rehab.

Investing more money in rehabilitation is evidence-based

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, government investment in drug rehabilitation is a smart decision.

Several conservative estimates suggest that every $1 invested in addiction treatment programs yields a return between $4 and $7 in societal benefit. (R)

The high return on investment stems from a combination of lower: (1) drug-related crime; (2) criminal justice costs; (3) theft; (4) interpersonal conflicts; (5) drug-related accidents (including overdoses and deaths) – post-rehab.

Additionally, most people who get proper treatment for substance use/abuse increase the country’s GDP (such as by getting jobs and becoming productive members of society).

3. Strict drug laws & harsh penalties

Singapore is known for having strict laws and harsh consequences associated with illicit drug administration, trafficking, and distribution.

Why? Because they recognize that fear of harsh penalties is a strong motivator to avoid buying and administering illicit drugs.

Although you won’t get gunned down “on site” Singapore for possession or usage of an illicit substance, you could get caned (literally beaten with a cane) up to 24 times – or executed. (R)

What is the drug law in Singapore? The Misuse of Drugs Act is a drug control law that classifies substances into 3 “classes”: A, B, and C.

- The law automatically assumes trafficking of a drug when a threshold quantity is exceeded (e.g. 30g cannabis).

- Law creates presumption that a person possesses drugs if he possesses the keys to a premise containing drugs.

- Any person found in or escaping from any place or premises which is proven or presumed to be used for the purpose of administering a controlled drug shall, until the contrary is proved, be presumed to have been administering the controlled drug.

- (In other words, merely associating with drug users puts you at risk of being convicted – incentivizing you to not associate with drug users).

- Law enforcement officers are allowed to search premises and individuals without a search warrant if he “reasonably suspects that there is a controlled drug” or “article liable to seizure.”

- (In other words, officers can conduct a search with no warrant if they suspect someone might be harboring controlled substances).

- Section 31 allows officers to demand urinalysis (i.e. urine sample + analysis) of suspected drug offenders.

- Section 8A prohibits any citizen or permanent resident of Singapore to administer any prohibited drug outside the country, and if found guilty, they’re punished as if they administered the drug within Singapore.

Under Schedule 2 of the Misuse of Drugs Act, any person importing/exporting the following quantities of drugs (or more) receives a mandatory death sentence:

- Opium: 1200g

- Morphine: 30g

- Heroin: 15g

- Cocaine: 30g

- Cannabis: 500g

- Cannabis mixture: 1000g

- Cannabis resin: 200g

- Methamphetamine: 250g

Any person caught manufacturing: morphine (or any variant); heroin (or any variant); cocaine (or any variant); methamphetamine – will also receive a mandatory death sentence.

Interestingly, the majority of executions in Singapore are for drug offenses. Since 2010 – 23 prisoners have been executed for drug offenses.

This policy is supported by many Singaporeans due to the fact that it strongly disincentivizes importation, exportation, and manufacturing of illicit drugs (via fear of death) – and is likely a key reason Singapore is winning its War on Drugs.

Whether you agree with this is irrelevant. If criminals know the consequence of getting caught importing/exporting drugs is an automatic death sentence, I’d guess that they’d be more likely to opt out…

Many Singaporeans believe that the consequence of “death” for serious drug-related offenses are a major reason Singapore has among the lowest rates of drug abuse worldwide.

What if you’re caught with just a small amount of an illicit drug in Singapore?

In this case, you won’t be executed – but penalties may be harsher than expected (e.g. up to 24 smacks with a cane and/or long-term imprisonment).

Quoted (from a Singaporean):

“Never once I was afraid of the strict laws. On the contrary, I always think they protect me from those who want to break the law. Caning may be barbaric to some but personally we have warned those would-be offenders that if they choose to break the law, they will be caned.”

Essentially, in Singapore citizens do not live in fear of strict laws and punishment because (most) don’t consider breaking the laws. Instead they support the strict laws.

If given the choice between “free but dangerous” and “strict but safe” – they’ll take the latter.

If laws were as strict and penalties as harsh in the U.S. – as they are in Singapore – I’d expect drug use/abuse to drop substantially.

Drug importers/exporters and traffickers are not living in fear of death in the U.S.

Furthermore, small-time drug users are not living in fear of being physically beaten with a cane or long-term imprisonment.

In U.S., the consequences for illicit substance possession and abuse are extremely lax (relative to Singapore) – and as a result, people don’t really fear the consequences.

Although you could end up doing a short stint in jail for possession of a certain substance, you won’t get beaten with a cane.

Moreover, there’s no uniformity across states in laws for specific illicit substances – or even consequences for endangering others while under the influence of legal drugs (e.g. drunk driving).

For example, in South Dakota – if you’re caught drunk driving, there’s no minimum sentence for your first 2 offenses, meaning, in theory – you could walk free with a proverbial “slap on the wrist.” (R)

Conversely, if you’re caught drunk driving in Arizona – you’ll be jailed for a minimum of 10 days for your first offense; minimum of 90 days for your second offense; and given an automatic felony for your third offense.

If the U.S. were serious about winning a War on Drugs – it would instate nationwide federal drug laws that override state laws with an emphasis on strictness and harshness of legal penalization.

4. Policing (Low corruption, adequate numbers)

Singapore has an estimated 170 police officers per 100,000 residents – which isn’t as high as the U.S.A. (~239 per 100K). (R)

That said, perceived police corruption in Singapore is among the lowest of any developed country with a score of 85/100 (higher = less corrupt) – U.S. scores 67/100. (R)

Assuming perceived corruption is a reliable indicator of actual corruption – it’s likely that Singapore has markedly lower corruption in policing than the U.S.

Lower corruption probably results in fewer police officers bribed by drug kingpins (e.g. cartels, dealers, etc.).

Having a reasonable number of police officers per capita (170 per 100K) combined with low rates of corruption is favorable.

However, things get even more favorable when there are strict laws and harsh penalties to strongly discourage drug manufacturing, imports/exports, trafficking, and administration.

Essentially, because: (1) drug laws are strict & penalties are harsh – fewer people engage in drug-related crimes AND (2) police corruption rates are likely low – it’s easier to win the war on drugs without necessarily significantly increasing the number of police officers.

If drug laws and penalties were lax – more people would do a subconscious cost-benefit ratio and more people would be willing to take the risk of manufacturing and selling drugs (e.g. if the consequences are short stints in jail, zero cane strikes, and there’s no fear of execution).

It’s also possible (this is a hypothesis – not substantiated with data) that police officers in Singapore have more effective (i.e. qualified) and efficient policing strategies – such that they’re able to “do more with less” – relative to the U.S.

Lastly, it is unclear as to how police in Singapore compare to police in the U.S. in funding per capita (i.e. government investment in police training and tech).

5. General consensus among Singaporeans

Although Singapore is a multiracial and multicultural country (76.2% Chinese; 15% Malays; 7.4% Indians) – the citizens and government have relatively homogenous (i.e. non-diverse) thought regarding drug laws.

In other words, there’s a consensus: most Singaporeans agree that the harsh penalties associated with manufacturing, importing & exporting, trafficking, and/or administering drugs – are beneficial to the country.

Why? Because these penalties reduce the likelihood that illicit drugs will enter and circulate within the country – and that Singaporean citizens will consciously choose to use them.

The homogeneity of thought extends beyond drugs – Singaporeans generally agree that adherence to “common decency” type rules helps benefit the country in terms of safety and business growth.

(As a result, there are substantial fines for littering, chewing gum, public smoking, jaywalking, and failure to flush toilets after use).

If Singaporeans had mixed sentiment (i.e. heterogeneity) regarding drug and “common decency” type laws, it’s likely that laws would be modified such as to make consequences less harsh (or not harsh at all).

More lax consequences would likely lead to a spike in drug-related crime and degrade the overall appeal of living in Singapore – Singaporeans know this and (smartly) choose to keep punishments for illicit drugs harsh.

Why else might Singapore be winning the war on drugs?

IQ, general education, culture, wealth.

Higher-than-average IQ and educational attainment yield greater wealth generation (on average) and smarter cultural decisions – ultimately creating a “virtuous circle” (i.e. favorable feedback loop).

Singapore is a first-world country – a highly developed, tech/finance hub in Asia.

The average IQ in Singapore is estimated to be ~108 (the highest average in the world, tied with Hong Kong). (R)

There’s probably a genetic component to IQ (to some extent) – but there’s 100% an environmental component (safe environment, quality education, access to clean water and nutritious food, good healthcare – increase odds of maximizing IQ).

This “environment” was created as a result of culture (including lawmaking) – possibly also IQ – and general accomplishments by the Singaporean people (businesses, etc.).

Because people are smarter (on average) and raised in favorable environments – likelihood of them desiring illicit drugs is lower.

How is Singapore continuing to fight against drugs in 2020?

In 2020, Singapore aimed to sharpen preventive drug education and rehab.

Why? There’s a rising threat of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) plus much misinformation and changing attitudes towards substances like cannabis.

The Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Home Affairs Amrin Amin stated:

“More than ever, we need strict laws to stay ahead of drug trends, robust enforcement, and effective preventive drug education.” (R)

In other words, Singapore realizes that many other countries are losing the War on Drugs – and thus have pretty much given up trying to enforce laws for certain substances (e.g. cannabis).

Singapore knows that while attitudes are shifting (e.g. mainstream acceptance of cannabis in social and medical contexts) – these shifts don’t automatically mean that the specific drug is devoid of adverse societal consequences and risk.

Moreover, Singapore understands the potential adverse consequences of legalizing various drugs (e.g. crime increases, lower productivity due to drug-related cognitive impairment, impaired operation of motor vehicles/heavy machinery, etc.).

As a result, Singapore is essentially doing the opposite of most major countries (i.e. losers of the War on Drugs) – until there’s an evidence-based or logical reason to do otherwise.

What about the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte?

Based on all data I’ve seen (assuming it’s accurate) the Philippines seems to be winning the War on Drugs by simply imposing one of the most savage consequences for drug dealing and usage: a shoot-to-kill directive.

Regardless of whether you agree with Duterte’s policy, the results speak for themselves – drug usage and corresponding crime rates have significantly decreased under his reign.

According to The Economist, Duterte stated:

“Find them all and arrest them. If they resist, kill them all” (regarding drug dealers and other miscreants).

News site Rappler reported: a 9.8% drop in all crimes under Duterte in his first year (2016-2017) with a 22.75% increase in killings (probably due to his War on Drugs). (R)

The Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) of the Philippines announced that the number of illegal drug users in Philippines declined by more than 50% (from 4 million in 2016 to 1.67 million in 2019). (R)

As of 2021, the Philippine Information Agency (PIA) reported a “63% drop in crime rate” under the Duterte administration. (R)

The accuracy of some data are controversial… “Top anti-narcotics officials in the Philippines admit that the data the president uses to justify his battle against drugs is flawed and exaggerated.” (R)

That said, the same officials quoted above believe the problematic statistics “don’t matter because the campaign has focused attention on a long-neglected crisis in the Philippines.”

Various wealthier, first-world countries and Human Rights Watch have criticized Duterte’s “War on Drugs” due to the killings of: (1) drug dealers and abusers AND (2) innocent people (killed wrongfully). (R)

It is argued that killing drug dealers/abusers is wrong – and that there’s no legal ramification for accidentally or deliberately killing innocents.

However, one could argue that countries who’ve clearly never had drugs under control and have significantly more wealth (e.g. U.S.) – should NOT be advising Philippines how to fight their “drug war.”

One could also argue that the drastic reduction in illicit drug use and drug-related crime as a result of this policy, saves significantly more innocent people than it kills.

More specifically, the “cost” of various innocent people dying wrongfully/accidentally substantially outweighs the “cost” that would’ve resulted from: (1) drug-related criminal killings; (2) drug overdoses (from more users); and/or (3) societal damage from failure to reduce illicit drug circulation and use.

Furthermore, 2 out of every 3 Filipinos believe that the number of drug users in their area has dropped since Duterte became president in 2016 – and thus his “War on Drugs” policy is extremely popular. (R)

81.6% of Filipinos approve of the government’s anti-drug campaign. (R)

Is this “War on Drugs” perfect? No. Have innocent people died? Yes. Is the death of innocents a bad thing? Yes.

In countries like the Philippines that don’t have as many resources to manage the problem – raising the stakes and imposing a harsh “kill on site” strategy to curtail drug dealing/use should be menacing enough to make a significant percentage of drug dealers/users discontinue or think twice.

Assuming the majority of police aren’t corrupt – this strategy should work well via induction of fear.

If you know that you can get shot on site for drug dealing – would you continue drug dealing? You might rethink your line of work.

Why might it be smart for poorer or developing countries like the Philippines to take an extreme/harsh stance against drug dealers and users?

They lack financial resources for: (1) legal proceedings (public judges/attorneys); (2) free drug rehab, counseling, behavior change; (3) housing people in prison; (4) investment in drug prevention.

If the Philippines treated all drug dealers/users like they’re treated in the U.S. – corruption wins out.

The drug dealers/users get good lawyers, beat the cases – and flood the streets with more drugs.

If they don’t win their cases, they’re draining taxpayer dollars by sitting in jail.

At some point, you need to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of the: negatives (innocent deaths, throwing a potentially useful life away due to lack of rehab, etc.) vs. (2) positives (fewer drugs in Philippines, lower crime rate, more tourism, increased business investment, etc.).

Drugs and crime are inexorably linked. Duterte’s “War on Drugs” has dramatically reduced crime.

I’ve contacted various Filipinos about the Duterte – some of whom strongly disagree with his methods – but nearly all have admitted that there’s significantly lower crime in their location and that they feel safer.

Duterte understands the fact that certain drugs, if freely distributed and/or used without consequence, can inflict massive societal damage – particularly in developing countries like Philippines.

Ultimately, regardless of what you think of his methods – they seem to be working.

In summary, the Philippines is a country demonstrating the power of harsh potential consequences (in this case – getting shot to death) in reducing general propensity to engage in drug dealing/usage.

Would as many people risk dealing and/or using illicit drugs in the U.S. if the consequence was getting gunned down on site without a trial?

I personally doubt it (if you can make an argument that they would – I’d love to hear it).

Have any countries won the “War on Drugs?”

The War on Drugs is never “over” (i.e. “won”) because there will always be: (A) people who want drugs AND (B) people who want to sell/distribute/get others hooked on drugs for profit.

That said, some countries are clearly “winning” the war on drugs insofar as strategies they’ve implemented to minimize illicit drug use and distribution have been successful.

In other words, rates of illicit drug usage and subsequent societal harms/tolls resulting from illicit drug usage are negligible.

Could the United States win a “War on Drugs”?

Yes – but deep down they don’t really want to.

If they wanted to win a “War on Drugs” or even drastically reduce crime, they’d (in no particular order):

- Enforce martial law

- Increase total policing (with anti-corruption units)

- Invest more in education/prevention

- Invest more in rehab

- Make drug laws stricter

- Impose harsher penalties for drug possession/use

- National drug laws (to provide consistency across U.S.)

In the USA there’s conflict between:

- Freedom (to do whatever one wants) or a libertarian-esque stance (e.g. adults should be able to use “any drug they desire” as long as it doesn’t harm others)

- Government regulation (e.g. making certain substances illegal)

- Drug use prevention and enforcement strategies

If the USA was extremely “fed up” with drug distribution and usage – it would (in no particular order):

Enforce martial law (in certain cities)

Much crime is drug-related (e.g. drug selling, territorial disputes, etc.).

Locking up criminals for general crimes, imposing harsher penalties for drug-related crimes, and getting as many drugs off the streets as possible – would decrease the opportunities of illicit drug usage (forcing people to shift focus to something more productive such as getting a job).

How could the U.S. go about doing this? Implement some sort of strategic martial law directive to target cities with the highest crime rates per capita.

Why? High crime generally equals high rates of drug use.

Annual crime rates per 100K people are highest in big cities such as: St. Louis (2K+ per 100K); Detroit (2K+ per 100K); Baltimore (2K+ per 100K); Memphis (2K+ per 100K); etc. (R)

Stationing military units in these cities (particularly in the most dangerous areas) as an adjunct to general police could go a long way to reducing drug-related crime in the U.S.

Anyone who is anti-martial law as a solution to the War on Drugs in the U.S. is probably not that serious about reducing the net adverse effect of illicit drug use in the U.S.

Why? The local police are overwhelmed in many of these cities and aren’t as equipped to get things under control as the military.

If martial law were implemented, I’d expect the numbers of drug manufacturers, dealers, and abusers to drop exponentially within a year or two.

That said, the military may need to be given special authorization to bend/break certain laws if necessary (as the U.S. legal process is bloated and some drug-related laws are downright ridiculous).

Enhance policing efforts

Because the drug laws in the U.S. aren’t very strict – penalties aren’t generally as harsh as countries like Singapore (e.g. canings and/or death for possession exceeding a certain quantity).

As a result: more people will take the chance of manufacturing, importing/exporting, distributing, and/or administering drugs – than would with harsher consequences.

If the U.S. is unwilling to modify drug laws (to make them harsher) and/or actually weakens its drug laws – drug-related crime will continue to rise.

For this reason, you’ll need significantly more police officers to manage the problem.

Increase number of police officers

U.S. needs more total police because a significant percentage of the population is not that afraid of the legal consequences associated with illicit drugs.

Crime rates are very high in certain cities – and the only way to get this under control is by increasing the number of police officers.

Evidence-based strategies (efficacy & efficiency)

The U.S. would benefit from studying and implementing policing strategies that are based on the latest scientific data.

The goal would be to increase (1) efficacy AND (2) efficiency – of policing (avoiding ineffective or suboptimally effective and inefficient methods).

Essentially, this would translate to “doing more with less.”

Improve police quality

Everyone can’t just “become a police officer” – there need to be reasonably rigorous standards for qualification (e.g. background checks, sufficient training, examinations, etc.).

Because I’m not a police officer and haven’t studied how to improve the “quality” of officers – I can’t make any specific recommendations.

(That said, at some point there’s likely diminishing returns – you need to have thresholds to weed out as many people who would be corrupt, suboptimal, or ineffective police officers as possible – while simultaneously getting as many people to become good police officers as possible).

Increase police funding

Although it’s become popular to want to “defund the police” among certain political parties (e.g. democrats) – this is probably not a smart idea.

I would actually recommend conducting an analysis to determine: (1) magnitude of funding (how well funded certain police departments are); and (2) spending efficiency (identify the most efficient ways to utilize monetary funds to combat crime).

Departments that are suboptimally funded should be given more funds and a professional should be appointed to determine how to most efficiently invest department funds (with the goal of reducing crime).

Moreover, I think ensuring that police have the latest technology to counteract crime (including drug-related) is essential.

Therefore, it might be wise to substantially increase police funding.

Increase anti-corruption units

Police corruption in the U.S. isn’t ideal.

The problem with police corruption is that corrupt officers may: receive financial bribes to directly help drug dealers (such as by not investigating them, leading an investigation in the wrong direction, actively facilitating certain deals, or by eliminating competition).

Corrupt police may also “rub off” on other police (such that corrupt officers recruit non-corrupt officers to become part of the corruption – and it continues to spread).

Invest in drug prevention & education (Money & Effort)

- Targeted strategies (relative to age)

- Evidence-based methods

- Cost-effective methods

- Re-evaluation of spending ROI (Increase efficiency)

- Enhance volunteer efforts

I’m not sure how much money and effort the U.S. invests in drug prevention and education per capita – relative to Singapore.

Nor am I sure of how the specific drug prevention and education investments made by the U.S. might differ in methods (which would impact efficiency and efficacy) relative to Singapore.

It’s possible that the U.S. invests similar amounts of money and/or efforts to Singapore per capita for drug prevention and education – but perhaps Singapore invests their money and efforts in more targeted, strategic ways.

If this is true, then essentially Singapore can essentially “do more with less” regarding drug prevention and education efforts.

It is known that Singapore educates citizens about drugs with strategies contingent upon age (and corresponding cognitive ability).

(Keep in mind that strict drug laws and harsh penalties for drug offenses augment drug prevention and education efforts – it’s easier to convince people that “drugs are bad” when there are harsh consequences for drug offenses).

According to Statista, the U.S. spent $40.4B (B = billion) in 2021 for “drug control” and the requested funding for 2022 is even higher. (R)

More than half of the requested budget in 2022 was for treatment of substance use disorders – the remaining half is allocated for prevention, interdiction, and law enforcement.

Analysis of the “Federal Drug Control Spending” reveals an estimated allocation of ~$2.8B for illicit drug use prevention – relative to $20B (treatment); $10B (drug law enforcement); $5B (interdiction); $1B (international drug issues). (R)

I’m not an expert on the most effective way to allocate ~$40B with the aim of reducing illicit-drug-related negative impacts (societal, financial, criminal, etc.) in the most efficient and effective way possible.

For this reason, I’m hoping that we are not “underspending” in prevention relative to what would be optimal.

Perhaps it would be worth experimenting over 5 or 10-year terms with allocation amounts to determine an optimal amount to invest in “prevention and education.”

Understand that “spending” is only part of the equation.

Throwing a lot of money at a problem generally helps to some extent – but it’s imperative that it is being spent on methods that are both: (1) evidence-based AND (2) cost-effective.

If, for example, a large chunk of money being spent on drug prevention is allocated to: (1) outdated, non-evidence based strategies and/or (2) cost-ineffective strategies – then we need to make revisions.

In other words, perhaps an organization or strategy involved in prevention is taking significantly more money relative to real-world value they’re providing (in terms of actually preventing drug use) – and nobody has bothered questioning why we’re giving them so much money.

What about volunteer groups? Singapore tends to have a lot of volunteer organizations working for free to educate vulnerable populations (youth, teens, young adults) on the deleterious consequences of illicit drug use.

It’s possible that a more collectivist culture (wherein people do things for the “good of the group”) has a natural propensity to yield more volunteer organizations than say an individualistic culture (people doing things for “their own good”) like in the U.S. (R)

Nevertheless, perhaps strategies to increase grassroots anti-drug volunteers in the U.S. would be of significant benefit for reducing illicit drug use.

Lastly, it’s possible that the group in charge of allocating government money towards drug prevention and education needs evaluation and critiquing.

SAMHSA estimates that the average effective school-based drug prevention program costs $220 per student – and ultimately saves an estimated $18 per $1 invested if implemented nationwide. (R)

Specifically, nationwide school-based effective programming in 2002 would’ve saved:

- $1.3B across state and local governments between 2003-2004

- $33.5B in social costs of substance-abuse-related medical care, other resources, and lost productivity over a lifetime

- $65B via preservation of quality of life over a lifetime

Note: The aforementioned amounts in savings will have increased substantially since the early 2000s (when this paper was published).

Invest in drug rehabilitation

The data are unanimous in suggesting that substantial investment in drug rehabilitation is smart.

Why? The greater the number of people who actually complete rehab – the lower the rates of drug-related crime and GDP loss (due to unproductive members of society).

Essentially, assuming former drug users complete rehab and stay sober – they’re likely to engage in less drug-related crime, have better overall health (physical and mental), have better relationships, and become productive members of society (working and earning money to increase GDP).

As was mentioned earlier in this article, conservative estimates suggest that every $1 invested in addiction treatment programs (i.e. rehabilitation) generates $4 to $7 worth of societal benefit. (R)

Over half of the “Federal Drug Control Spending” budget (~$20B) was allocated to “treatment” for illicit drug abuse/addiction. (R)

It’s possible that it could be beneficial to spend even more on drug abuse/addiction treatment via rehabilitation.

That said, spending money on drug rehabilitation does not necessarily mean that people will enter rehab.

It is thought that addicts without health insurance and devoid of jobs may be unable to enter rehab – as rehab centers may require basic insurance or some sort of co-pay.

For this reason, perhaps it would be smarter for the government to allow free rehabilitation regardless of insurance status – or even help addicts get insurance in rehab.

Additionally, it would probably be smart to follow Singapore’s approach to rehabilitation.

Singapore essentially forces all drug addicts (against their will) to enter rehab.

(The U.S. cannot usually force anyone to enter rehab against their will. Only doctors and family members can do this in certain states – and this is essentially impossible if the addict’s location is unknown).

Furthermore, Singapore follows up with all persons who go through rehab and helps them successfully reintegrate in society (e.g. get jobs, maintain routine, avoid drugs, etc.) – I’m not sure if the U.S. has the same method here and may not hold addicts as accountable.

Analyzing both rehabilitation spending AND rehabilitation strategies (to ensure they’re evidence-based and cost-effective) is key.

We want to be spending as much as possible on rehabilitation provided the amount spent is providing a good ROI (in terms of net societal benefit).

Stricter drug laws

The U.S. does NOT have very strict drug laws when it comes to illicit drugs. As a result, people aren’t as concerned about the consequences.

Making drug laws stricter can be done in several ways: (1) lower threshold drug amounts for penalties; (2) reduce the number of substances that are legal; and (3) increase the harshness of illicit drug-related penalties (i.e. consequences).

Some general ideas can be taken from Singapore’s drug enforcement strategies and be applied to the U.S. if the aim is to seriously win the War on Drugs.

(Keep in mind that the U.S. wouldn’t need to copy their drug laws verbatim – but various modifications of laws may be useful).

What are some proposals?

- Death sentence (?): Mandatory death sentence for possession of a certain quantity (e.g. grams) of an illicit drug (importing, exporting, trafficking, etc.).

- Physical punishment (?): Add some sort of physical punishment to the law wherein a person is hit if they’re caught with a certain substance or quantity of that substance.

- Assumed trafficking: If a certain threshold of a drug is exceeded, assume the person is trafficking. (This seems reasonable to me – and maybe the U.S. already does this).

- Assumed possession: If an adult possesses keys to a premise containing drugs – assume that person is responsible for the drugs (unless proven otherwise).

- Assumed usage if at certain premises: If you’re associating with a drug dealer (e.g. at the dealer’s house a lot) – you’d be assumed to be using an illicit substance along with him (unless proven otherwise). This disincentivizes non-users befriending drug users.

- No warrants required: Law enforcement officers should be able to legally search premises and individuals without a search warrant if there’s “reasonable suspicion” that the person has a controlled drug.

- Urinalysis demand: Suspected drug offenders can be ordered to complete a urinalysis at any time (“on the spot”) without explanation.

Keep in mind that these are just ideas to consider.

Obviously the only people who should actually be “worried” about such policies are those addicted to various drugs.

If you’re not addicted and don’t associate with drug users/dealers – you should have nothing to worry about.

Are Americans intelligent enough to vote on drug laws?

The U.S. is a “free country” but most people voting on the legalities of certain substances are completely clueless about the potential societal harms that could result from legality.

(Let’s single out cannabis as an example).

Potential societal harms from cannabis legalization include (but are not limited to):

- Increased mental illness; cognitive/memory impairment

- Lower empathy

- Car accidents (from driving under the influence)

- Lung diseases (from increased smoking)

- Lower average IQ (altered brain development from chronic use as teenager)

Additionally, most people do not understand that cannabis, being a plant, is not chemically consistent (i.e. standardized) – and therefore physical and mental effects could be wide-ranging based specifically on the specific “strain” of plant grown and/or specific leaf/leaves extracted from the plant.

Lastly, from a scientific perspective, claims regarding health benefits of cannabis are exaggerated (at this time) relative to the quality of evidence for these claims – and risks have been generally overlooked or not seriously considered. (R)

Keep in mind I’m not anti-cannabis legalization – I just believe that most people are only considering potential benefits such as: job creation, fewer incarcerations, less funding for criminals, possible health benefits.

Ideally, people would seriously consider both the potential benefits AND potential drawbacks – and conduct some sort of societal cost-benefit analysis (i.e. do the net societal benefits outweigh the net societal harms).

Impose harsher penalties

This ties in with “stricter drug laws” but I felt it warranted its own analysis/discussion.

If the U.S. were serious about reducing both total crime and drug-related crime (total crime reduction results from fewer drugs) – it would revise laws to impose harsher penalties for those who: (1) manufacture; (2) import/export; (3) distribute/traffic – illicit drugs.

Those who are simply abusing or addicted to various drugs need not be subject to these harsh penalties – because they’re not the ones flooding the country with drugs.

Essentially we need to make those who are intentionally flooding the country with drugs extremely afraid of their actions.

The key here would be to take a page out of Singapore and/or the Philippines book – wherein there’s fear of physical harm (e.g. beating, caning, etc.), hard labor, OR even death (such as license to kill drug dealers for police – or a mandatory death penalty for possession of certain drug quantities).

For example, let’s say you catch a drug kingpin like El Chapo. Why waste time putting him through the legal system?

There should be special laws in place wherein known kingpins can be legally executed “on site” (saving taxpayer money via court systems, imprisonment, etc.).

- Hard labor (?): Force criminals to engage in hard labor for a specific number of hours (and to a specific quality standard) as a result of drug-related crimes. The hard labor would be done with zero compensation. (Think community service but significantly more demanding and tougher). However, this might be too dangerous to supervise.

- Physical harm: Transient physical harm such as like is inflicted in Singapore with a cane can be a good way to teach someone a lesson. Essentially the brain associates “pain” from the physical harm with the consequence of doing something unfavorable (e.g. dealing drugs) and decides to discontinue the behavior.

- Death (?): Perhaps having a mandatory death sentence for possession of large quantities of drugs (e.g. intention to distribute) would be a good thing. This would discourage people from manufacturing and dealing large quantities of illicit substances.

The goal of the harsher penalties is to clearly induce fear (why? it motivates behavior).

The less fear people have of a specific law – the more likely they’re going to break it.

(Imagine if there were a mandatory death sentence for getting caught going 30 mph above the speed limit. Do you think people would intentionally go 30 mph above the speed limit? I don’t.)

In the Philippines there’s literally a “shoot to kill” type directive for any drug abuser or dealer who resists arrest.

Does the U.S. need to employ a Duterte-style “shoot-to-kill” order for any drug user/dealer who resists arrest? Probably not.

However, the U.S. should come up with harsher consequences for drug users (perhaps depending on the quantity of a drug in possession and offense number) – if winning the War on Drugs is an actual goal. Would the U.S. actually do this? Doubtful.

In 1994, Michael Fay (an American teenager) vandalized property in Singapore (spray-painting a judge’s personal car) and was sentenced to 6 lashes with the cane (the U.S. government negotiated this sentence down to just 4 lashes).

A majority of Americans were outraged that “caning” was his punishment for a variety of reasons (he was: American; a “minor”; and the spray-painting damage wasn’t permanent). (R)

Why am I using this as an example? Because it showcases the fact that most Americans are outraged at serious punishment for criminal behavior.

However, I admittedly could be wrong here in my thinking that harsher punishment would actually deter crime.

The Chinese expression “kill the chicken to scare the monkey” applies here.

The goal is to make an example of criminals and showcase the serious penalties that result from breaking drug-related laws – ultimately so that fewer illicit drugs enter, circulate, and are administered in the U.S.

The U.S. Department of Justice and USNW (Sydney) are in agreement suggesting that harsher punishments do NOT deter crime. (R1, R2)

However, the idea of harsh punishment may need to be clearly defined.

Although extended prison terms are clearly harsh (in some respects) – they’re not necessarily the same as: (1) forced labor, (2) physical harm (e.g. canings), and (3) automatic death.

I’d argue that people might not be as afraid to “go to prison” (even for an extended term) as they would be of forced labor, physical harm, and execution.

That said, if I’m incorrect here – why are drug-related crimes so low in Singapore?

Why did drug-related crimes drop significantly in Philippines after Duterte give police authority to kill drug abusers and dealers?

(Keep in mind that I’m assuming the drug use/crime data provided from various government agencies in Singapore and Philippines are accurate).

I’m willing to admit that “harsh penalties” for drug offenses may be a suboptimal strategy.

That said, if someone were to analyze all countries based on harshness of penalties for drug-related offenses – would net societal benefits outweigh the drawbacks of such policies?

Emeritus professor David Brown suggests that instead of harsh penalties, we’d be better off investing in social programs to: decrease unemployment, increase adult education, provide stable accommodation, increase earnings, and improve mental health treatment. (R)

That said, Scott et al. (2020) reports that “reward and punishment both work independently, as well as together” – in influencing behavior. (R)

National drug laws (override state laws)

In theory, the U.S. should implement national laws that override most state laws so that there’s uniformity across the country to disincentivize illicit drug-related crime.

If penalties are lax in one state – then that state will likely have a bigger drug problem relative to one with harsher consequences.

As a result, you’ll have certain “drug zones” or “hotbeds” throughout the country wherein drug use/abuse is rampant due to legal inconsistencies.

Right now, there’s a complete lack of consistency with regard to: the legalities of various illicit substances; threshold quantities that qualify as criminal; and penalties for manufacturing, importing & exporting, distributing, possessing, and/or using certain illicit substances.

Assuming the U.S. could implement strict universal drug laws and enforce these laws throughout the entire country – it would probably go a long way towards reducing the massive societal burden (financial, criminal, productivity loss, poorer health) resulting from illicit drugs.

That said, the thought of “universal” drug laws across the U.S. seems like nothing more than a pipedream due to regional differences in thoughts/opinions among citizens – and widespread belief in “freedom” to use whatever drug one desires.

The “freedom” type thinking is problematic insofar as most people who emphasize “freedom” aren’t able to think several steps ahead and consider the fact that many drug users endanger sober persons as a result of:

- Psychological and behavioral unpredictability (while under the influence)

- Driving under the influence, committing crimes to buy more drugs (fueling addiction)

- Being unproductive or cognitively impaired due to drug use and not working, etc.

Invest in social programs (?)

The U.S. doesn’t have an unlimited budget, however, some have suggested that drug-related crimes would decrease substantially if the U.S. invested more on social programs.

Though investing more in drug prevention and education AND drug rehabilitation are evidence-based ways to decrease the societal toll of illicit drugs – it may be worth considering investing more money in social programs.

Emeritus professor David Brown argues that we’d be better off investing in social programs than imposing harsh legal penalties for crimes. (R)

I’d ask David Brown why it wouldn’t be beneficial to do both.

Perhaps the combination of harsher legal consequences AND increased social program spending would be of greater benefit than either as a standalone.

Why does David Brown argue for spending more on social programs?

This quote sums it up: “It’s roughly $300 per day to keep someone in jail, whereas, it’s roughly $23 a day for someone in community corrections.”

The money could go back to schools, hospitals, supportive housing, drug/alcohol programs, and employment programs.

Is what David Brown is arguing based on evidence – or just a hypothesis?

Various European countries have more social programs than the U.S. – but most of these countries are less populated, ethnically homogenous, less diverse, and have lower illicit drug use.

I think it may be worth conducting some sort of 5 to 10-year study allocating more money towards social programs to determine whether this significantly decreases illicit drug-related crimes.

Moreover, I’d hire someone to oversee social welfare spending to ensure that the money is spent as efficiently as possible with regard to maximizing societal benefit.

I would guess that one reason many people end up using illicit drugs is as a means to cope with some sort of life stress, trauma, etc.

Increasing social programs may enable these people to cope more effectively and prevent a subset from pursuing illicit drugs in the first place.

As of 2019, the 10 biggest spenders on “Social Welfare” (as a percentage of GDP) included (R):

- France (31.2)

- South Africa (30)

- Belgium (28.9)

- Finland (28.7)

- Denmark (28)

- Austria (26.6)

- Sweden (26.1)

- Germany (25.1)

- Norway (25)

- Spain (23.7)

The U.S. scored 18.7 – which was ranked 22 of 36 countries listed.

Note: Some might be surprised to learn that the U.S. was ahead of Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Israel, Switzerland, Italy, Ireland, South Korea, Chile.

Moreover, in “net social spending” – the U.S. ranked #2 behind France.

If the social program spending argument to combat drug use and crime is valid – why does the U.S. have a bigger drug problem (per capita) than countries spending less than the U.S. on social welfare?

I guess that some experts might hypothesize that U.S. spends money far less efficiently/effectively on “social welfare” than other countries listed and that’s why it’s struggling in certain ways.

Still, David Brown’s thesis (more social spending = greater benefit) doesn’t always seem to hold true – and this is perfectly exemplified by Singapore.

The Government of Singapore spends only ~16.7% of its GDP on all of its social programs – a figure that’s less than half as much as European and Scandinavian programs. (R)

By Brown’s logic – Singapore should have a much higher crime rate than countries who spend more on Social Programs – but it’s the exact opposite.

And one could legitimately argue that the reason it’s opposite is because Singapore implements harsh penalties (e.g. caning) for behaviors that degrade society and encourage disobedience (e.g. littering, chewing gum, failing to flush toilets, drug use, etc.).

Most residents and visitors (e.g. tourists) of Singapore are very aware of its penalties – and so are essentially better behaved and less likely to consider engaging in socially destructive behavior (e.g. drug use).

- Note #1: It’s easier for some of these countries to spend a lot on social welfare as a percentage of GDP due to leaching off of other countries for military security, etc.

- Note #2: It’s unclear as to how each of these countries differs in spending efficiency (i.e. maximum societal ROI relative to investment).

Additional considerations regarding War on Drugs in U.S.

- Interventions may need nuance: Perhaps the most efficient/effective methods for decreasing the societal toll resulting from drugs (legal and illegal) are contingent upon the specific country or region within the country. Nuanced strategies based on culture, laws, and demographics may be better than “blanket” strategies – given state-specific differences.

- Encourage general civic obedience: I’m of the belief that encouraging civic obedience with harsher penalties for disobedience like Singapore (e.g. littering, public smoking, failing to flush public toilets, etc.) generally encourage better behavior – which may be tangentially related to decisions to use drugs.

- Rewards (?): Though punishment can be an effective means to influence behavior – so can reward. Perhaps it would be beneficial to incentivize people such as former addicts (whether it be financially, with food, etc.) to “stay clean.” (Not sure how this would be done – just something to consider).

- Experimental strategies: Continue experimenting with novel strategies with the aim of minimizing negative societal impacts of drugs.

- Regularly evaluate ROI (money & efforts): An expert panel of scientists should regularly evaluate (at set intervals) the societal ROI of monetary and effort investment with regard to minimizing negative societal consequences resulting from drugs.

- Robotics & AI: Robots could be used to help detect and detain drugs from criminals in high-risk areas. AI can be used to evaluate which strategies are likely to be most efficacious in reducing the societal burdens resulting from both legal and illicit drug use.

Overall, I think if the U.S. wanted to – it could improve in many ways to decrease the societal burden resulting from drugs (both legal and illegal).

If you have any additional thoughts or ideas for reducing the societal burdens stemming from drug use (legal and illegal) – I’d love to hear them.

Understand that I’m NOT an expert and some of the ideas proposed have basically a 0% chance of being implemented in the U.S.

What’s my stance on drugs?

I have a somewhat pro-libertarian stance on drug use – reserved for educated, mentally-competent adults (with strings attached) as long as they will NOT:

- Endanger the health of others

- Endanger their own health (yes, people should be prevented from damaging their own health)

I definitely would like if all drugs were legalized, but the reality is that a majority of adults in the U.S. would be adversely affected by this legislation.

Why? Here’s a hypothetical scenario. Let’s say heroin is now legal and can be added to drinks for sale at gas stations/convenience stores.

For the sake of simplicity, we’ll call the drink “Canned H.”

Canned H is now aggressively marketed such as with online ads, TV commercials, billboards, etc.

A subset of highly-educated people who know that heroin is among the most physically and mentally addictive drugs – will never bother trying the drink.

However, your average person (particularly if uneducated, young, vulnerable, or genetically-inclined to “take risks”) will probably end up trying it.

Though a subset of drinkers will have adverse reactions to it (e.g. vomiting) – which is common with opiates – a big percentage will become “hooked” on the Canned H – such that it’ll consume their thoughts/life.

If we think several steps ahead – frequent “Canned H” consumption will not only damage the drinker’s physical health and hormones – but they’ll be unfit to work (cognitive deficits and inability to safely operate heavy machinery, etc.).

As a result, GDP will likely drop and crime rates will increase (more Canned H drinkers will become criminals to support their addiction).

Additionally, analogous to “junk food” creation (high sugar, high fat, high salt, crunchy textures, etc. – hyperpalatable foods) by scientists, if drugs were legal – companies would be: (A) hiring scientists to maximize addiction potential AND (B) hiring the best marketers to get people trying (and hooked).

Giving people just one free sample of “Canned H” would generate lifelong customers.

Therefore, my stance is that some (probably many people) need to be prevented from having the choice to try Canned H.

(As a result, I think that making certain substances illegal and imposing penalties is smart).

Moreover, I tend to think that most educated and intelligent people can pretty much any drug (if really desired) such as by traveling to another country, verifying purity, and using responsibly.

How to decide whether a drug should be legalized…

Personally, I’d like experts to develop a consensus:

Harm potential scale

Financial, cognition, health, societal, addictiveness, death/overdose risk, etc.

On average, how likely is this substance to cause harm – and what is the average magnitude of harm? (Rank on scale of 1-10).

Health potential scale

Enjoyment potential could be included here.

On average, how likely is this substance likely to improve health or induce pleasure? (Rank on scale of 1-10).

Drugs that cause negligible or no harm (on average) or even provide health benefits (on average) should be legal regardless of addictiveness.

Caffeine

For example, caffeine is obviously addictive.

However, it causes virtually no harm when consumed in certain formats (e.g. coffee, green tea, etc.) below a certain daily dose (e.g. 300 mg) – and is actually associated with health benefits (e.g. cognitive enhancement).

Using my logic – we should keep caffeine legalized.

Cannabis

What about “cannabis” (i.e. marijuana)?

This is more nuanced due to the fact that “cannabis” is not a chemically predictable substance (phytocannabinoid content will vary depending on the specific strain – and so will the effects).

There’s subtle evidence that certain forms of cannabis and specific cannabinoids (i.e. cannabis components – e.g. cannabidiol) may help treat certain medical conditions – but there’s inconclusive evidence.

There’s some evidence indicating that cannabis may increase risk of traffic accidents (e.g. driving high), impair long-term memory, increase risk of neuropsychiatric disorders (in vulnerable populations), and decrease empathy (i.e. reduced emotional processing). (R)

Therefore, I’d like qualified experts to be making the laws here – and maybe devise some criteria for which “cannabis” is legal to use (e.g. must contain less than X% of specific phytocannabinoids).

Perhaps certain phytocannabinoids could be legalized and others should be restricted for medical use only?

Nicotine

Nicotine is among the most addictive legal drugs in the world – yet it’s unclear as whether nicotine is harmful as a standalone agent (e.g. nicotine patch).

Some research suggests that nicotine decreases risk of cognitive decline and dementia – but other research indicates nicotine may be carcinogenic – the jury is still out.

(There aren’t enough data to make any strong conclusions re: nicotine).

Cigarettes

Cigarettes are obviously horrible for health, and nicotine makes them addictive, but the nicotine generally isn’t considered responsible for a bulk of cigarettes’ adverse health effects (other more carcinogenic ingredients within the cigs are).

If we were able to ban all cigarettes – I think this would be a net positive for societal health and some smart people agree with me (e.g. Peter Singer). (R)

(I’m 100% okay with an outright cigarette ban – but the government probably wouldn’t do this because they’re retaining more money via Social Security from smokers dying young).

Alcohol

I’m of the mindset that alcoholic beverages are a double-edged sword – some potential benefits (e.g. social lubricant, pleasure, etc.) for a subset of the population.

However, there are serious potential consequences if not consumed responsibly (e.g. physical altercations, bad decision making, cirrhosis of the liver, depression/anxiety, drunk driving, endangering others while operating heavy machinery at work, etc.).

Alcohol is relatively addictive as well – particularly for a subset of drinkers.

What I’d do is enforce extremely harsh penalties for getting caught driving drunk OR any alcohol-related crimes (e.g. assault under the influence of alcohol).

Theoretically, making consequences harsher should reduce odds of alcohol overconsumption.

In sum, I’d defer to scientists to help craft the laws regarding various drugs.

The focus should be on a combination of: (A) harm potential (health, society, GDP, etc.); (B) health potential (how might the substance benefit one’s health or enjoyment); and (C) addiction potential.

Determining legality…

Harm + Zero health benefit = Illegal.

Any substance with (1) moderate-to-high harm potential and (2) low-to-no potential health benefits should be made illegal with harsh legal penalties (canings, prison time, imposed community service, etc.).

Moderate health potential = considered.

Any substance with at least moderate-to-high health potential should be taken into consideration for restricted usage (e.g. educational classes/tests before using the drug, medical guidance, etc.) – even if it may have some harm potential.

(The aim here would be to strategically minimize harm potential via requiring certain stipulations for using).

Substances with extremely limited or zero harm potential (I’m not sure if any substance has universally “zero” harm potential – but some substances have virtually “zero” harm potential “on average” a.k.a. for most consumers) – should be fully legalized if they aren’t already.

What about this case: moderate harm potential vs. moderate health potential? Like I said, I’m not the expert.

To be fair, I think it would be wise to require an educational “passport” and/or certain conditions being met to use any drug with moderate harm potential (even if it has moderate health potential).

Thereafter, I’d suggest imposing harsh penalties on people who either endanger or harm others while using any drugs with moderate harm potential.

That said, those are just some of my thoughts here – and I’m not claiming to be an expert.

I’d like the actual experts to make the rules/laws based on a more comprehensive analysis of each substance.

The ultimate goal would be to improve the health (physical and mental), productivity, and health span of everyone in the country.

Where do I think the U.S. is headed with regard to drug policy?

The U.S. has essentially given up trying to win a war on drugs.

A majority of the populace believes that cannabis and psychedelics should be legalized – either for personal enjoyment, medical benefits, or a combination thereof.

- Decriminalization: Most drugs in the U.S. are headed towards “decriminalized” status – particularly for those who administer or possess small quantities. In other words, if you have a small amount of cocaine for personal use – it’s probably not worth sending you to jail and increasing legal system bloat (lawyer, court date, etc.).

- Big business (jobs & tax revenue): The Federal and State governments realize there’s a lot of jobs that will be created and tax revenue generated from legalizing certain substances (e.g. cannabis). There’s a “FOMO” aspect to this too – if a neighboring state has cannabis legalized: more people may move there and tax revenue should be far greater than places where illegal.

- Legalization (of many drugs): Cannabis is gradually becoming legalized in more states because a significant percentage of the population enjoys using and/or believes it has medical benefits. Psychedelics are being recognized as treatments for PTSD, anxiety, refractory depression, and end-of-life depression.

U.S. should focus on harm prevention & reduction

Based on this, I think the U.S. should do is concentrate efforts towards preventing and minimizing potential (societal) harms resulting from legal and decriminalized substances.

More specifically, the U.S. should continue educating users on the potential negative impacts of various legal and illegal substances on:

- Health (physical and mental)

- Productivity (e.g. lower motivation, addiction, cognitive impairment)

- Cognitive function (short-term and long-term)

- Psychology and behavior (e.g. unpredictability, psychosis, potentially harming others, etc.)

- Safe ways & settings for use of certain drugs

- Likelihood to commit a crime while under the influence (e.g. cocaine)

I also think that if certain drugs are legal (alcohol, cannabis, etc.) there needs to be very harsh penalties for anyone who endangers the life of another person while under the influence.

For example, if you decide to drive under the influence of alcohol or cannabis and you get into an accident (due to intoxication) – you should be physically beaten (e.g. caned), subject to hard labor, and/or imprisoned for an extended duration.

Perhaps greater freedom to use drugs should come with even greater responsibility.

Current penalties should be consistent across the U.S. and far harsher than they currently are – in my opinion.

Do you have any thoughts on the “War on Drugs”?

- Why do you think the “War on Drugs” has failed in the U.S.A.?

- Do you agree with my assessment that it’s due to lack of policing and relatively lax penalties? (Why or why not?)

- If you were omnipotent and could change the U.S. drug laws in any way(s) you desired, what would you do? And why? (Give a reasonable explanation).

- Have you thought about the fact that “legalizing” all drugs could potentially endanger you and your family? (Such as more people driving under the influence of certain substances e.g. heroin – or death rates increasing because TikTok teens are doing the Fentanyl challenge?)

- If we were to legalize all drugs, in my opinion, there would need to be extremely harsh penalties for anyone who endangers others while under the influence (unless it was proven that they were “drugged” against their will by another party).

- For example, if you’re caught driving under the influence of heroin – you’d get caned (or physically inflicted punishment) and/or a long-term sentence with government-mandated prison labor. (This should make people think twice about the consequences of their usage).