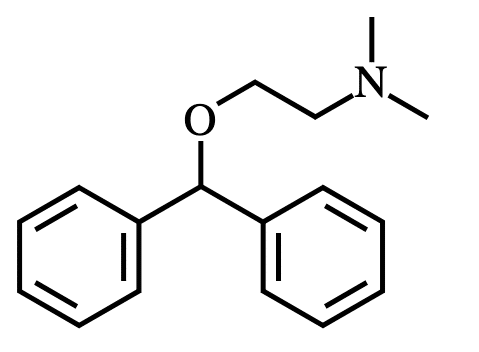

Diphenhydramine is a first-generation ethanolamine antihistamine developed by George Rieveschl and was approved for usage in 1946.

In the U.S. and Canada – diphenhydramine is the primary active ingredient in the over-the-counter medication “Benadryl.”

As of 2017, diphenhydramine was the 241st most commonly prescribed medication in the U.S. – exceeding 2M prescriptions.

Total usage of diphenhydramine is likely greater than the number of prescriptions would suggest given that it is sold over-the-counter (OTC).

Diphenhydramine is commonly used to treat allergies, itchiness, common cold, motion sickness, and extrapyramidal reactions.

However, because it is sedating, many wonder how well it works for the enhancement of sleep and management of insomnia.

How does diphenhydramine enhance sleep & treat insomnia? (Mechanisms)

H1 receptor inverse agonist

Diphenhydramine induces a sedative/hypnotic effect primarily by acting as an inverse agonist at the H1 histamine receptor site.

In other words, it binds to H1 receptors and induces a pharmacological effect the opposite of a conventional H1 agonist.

Inverse agonism and blockade of H1 receptors in the cortex and ventrolateral preoptic (VLPO) nucleus in the hypothalamus turns the sleep-wake switch “off.”

The absence of the stimulating effect of histamine in these regions promotes sedation and subsequent sleep.

Other less significant actions…

mACh receptor antagonist

Diphenhydramine also acts as a competitive antagonist at a variety of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (M5, M4, M1, M3, M2 – in order of highest-to-lowest binding affinity).

This facilitates an “anticholinergic” effect – blocking the action of the stimulatory neurotransmitter “acetylcholine.”

Serotonin receptor modulation (?)

Diphenhydramine appears to modulate activity of 5-HT2A receptors and, to a lesser extent, 5-HT2C receptors.

The degree of serotonergic modulation is dose-dependent such that low doses won’t influence these receptors much.

Diphenhydramine for Sleep & Insomnia (Research)

Included below are some studies that examined the effect of diphenhydramine on sleep or for the treatment of insomnia.

OTC Agents for the Treatment of Occasional Disturbed Sleep or Transient Insomnia (Systematic Review of Efficacy & Safety)

Culpepper & Wingertzahn (2015): “A review of randomized controlled studies over the past 12 years suggests commonly used OTC sleep-aid agents, especially diphenhydramine and valerian, lack robust clinical evidence supporting efficacy and safety.” (R)

- Conducted a systematic review of the literature up to 2014 and included data from randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials that utilized overnight objective (polysomnography) or next-day participant-reported sleep-related endpoints – and that included healthy participants with or without occasional disturbed sleep or insomnia.

- A total of 3 studies met inclusion criteria that specifically involved diphenhydramine.

- Clinical trial data for diphenhydramine suggested limited beneficial effects.

What can we learn from this study?

There haven’t been many quality placebo-controlled RCTs evaluating the efficacy of diphenhydramine for the treatment of insomnia or the enhancement of sleep (just 3 studies met inclusion criteria for this systematic review).

Because the data are limited here, it’s difficult to know how effective diphenhydramine truly is for the treatment of insomnia – particularly over a long-term.

Culpepper & Wingertzahn noted “limited beneficial effects” meaning diphenhydramine might be efficacious to some extent – but they aren’t entirely sure.

Moreover, researchers stated that there’s a lack of evidence to confirm the safety of diphenhydramine usage for insomnia.

Perhaps there are specific “safety” concerns relevant to insomnia treatment, however, diphenhydramine is considered safe enough to be sold “over-the-counter” sans prescription.

Other non-systematic reviews… (lower quality data)

Katayose et al. (2012): Antihistamines (including diphenhydramine) taken before sleep significantly increase subjective and objective sleepiness and significantly reduce psychomotor performance the next day – generating clinically identifiable sedative-hypnotic carryover effects. (R)

- Conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involving 22 healthy male participants assigned to receive 4 drugs at distinct time-points – each separated by more than a 1-week interval.

- The drugs: Zolpidem (10 mg), diphenhydramine (50 mg), ketotifen (1 mg), placebo.

- Evaluations: Polysomnography, subjective sleepiness, objective sleepiness, psychomotor performance.

- Results suggest that risk-benefit calculations should be conducted in antihistamines that easily cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for alleviating secondary insomnia associated with allergies.

- Compared with placebo, diphenhydramine had significantly longer REM latency (99.9 minutes vs. 138.5 minutes) and reduced % REM (20.5 minutes vs. 16.2 minutes).

- No differences in other sleep parameters (total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, time spent in non-REM sleep stages, wake after sleep onset, arousal, etc.) were found between diphenhydramine, zolpidem, ketotifen, and placebo.

What can we learn from this study?

In healthy men there doesn’t appear to be significant benefit on sleep parameters from taking diphenhydramine on an intermittent basis.

Additionally, there appear to be significantly more negative effects associated with diphenhydramine such as: (1) higher next-morning/next-day sleepiness & (2) greater psychomotor impairment – relative to both placebo and zolpidem.

Lastly, diphenhydramine appears to alter REM sleep by (1) increasing REM latency and (2) reducing % of REM sleep – whether this is detrimental to health remains unclear.

Glass et al. (2008): “Temazepam is more effective than diphenhydramine when compared with placebo at the doses tested, although this advantage is mitigated by the risk of falls associated with temazepam use.” (R)

- A randomized, controlled, crossover study compared 14-night treatment with temazepam (15 mg), diphenhydramine (50 mg), and placebo – in 20 elderly patients (70+ years old) with insomnia.

- Measures: Subjective sleep assessments (sleep diary); morning-after psychomotor impairment; morning-after memory impairment.

- Results: Diphenhydramine improved sleep by significantly reducing the number of nighttime awakenings relative to placebo – but had no impact on other aspects of sleep. However, it had no effect on sleep architecture (Stages 3 & 4 or deep sleep) – which may explain its lack of significant effect on sleep quality.

- Conclusion: Findings do NOT support the hypothesis that diphenhydramine is a practical sedative-hypnotic alternative to benzodiazepine for elderly patients.

Morin et al. (2005): “The findings show a modest hypnotic effect for a valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine relative to placebo.” (R)

- A total of 184 adults (110 female; 74 male; ~44.3 years of age) with mild insomnia participated in a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized parallel-group study at 9 sleep centers in the U.S.

- Interventions: (1) Valerian + hops for 28 days (N=59); (2) placebo for 28 days (N=65); (3) diphenhydramine (50 mg) for 14 days followed by placebo for 14 days (N=60).

- Measures: Sleep parameters determined by daily diaries and polysomnography, clinical outcome ratings from patients and physicians, and quality of life measures.

- Results: Modest improvements of subjective sleep parameters with diphenhydramine and valerian-hops combination supplements, but few group comparisons reached statistical significance.

- Diphenhydramine produced significantly greater increases in sleep efficiency and a trend for increased total sleep time relative to placebo during the first 14 days of treatment.

- Conclusion: Diphenhydramine might be useful as an adjunct treatment for insomnia.

Kudo & Kurihara (1990): “Diphenhydramine appears to be effective in the treatment of insomnia, but the appropriate dosage will depend upon previous medical treatment of insomnia.” (R)

- 144 psychiatric patients with insomnia received diphenhydramine in a double-blind procedure at dosages of 12.5 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg.

- The general condition of the patients with insomnia was at least “slightly improved” (after treatment with the test drug for 2 weeks) in:

- 5% (12.5 mg group)

- 60% (25 mg group)

- 4% (50 mg group)

- Side effects were documented in 11 patients (7.6%) but were not severe.

- Interestingly there were no symptoms suggestive of drug dependence throughout this study.

- Degree of improvement was not influenced by specific patient background factors other than whether the patient had previously received treatment for insomnia.

- Patients who had NOT previously received treatment for insomnia experienced more significant improvements.

What can we learn from this study?

Among psychiatric patients with insomnia, diphenhydramine effectively reduces the insomnia at dosages of 12.5 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg. Its effect seems most robust in patients who hadn’t received previous treatment for insomnia.

Although “dependence” was not observed, it’s possible that 2 weeks was too short to detect dependence. Note: Dependence is NOT the same as tolerance – but researchers in this study defined it similarly.

It’s possible that ongoing treatment with diphenhydramine generates some degree of tolerance – particularly when used for longer than 2 weeks.

One relevant question to ask is why didn’t patients previously treated for insomnia respond as well as treatment naïve patients to diphenhydramine?

The answer is unclear but may be due to: (1) cross tolerance to diphenhydramine via usage of other medications (such as via H1 receptors) OR (2) significantly less severe insomnia due to getting it under control with prior treatment such that robust improvements were less noticeable.

It’s important to note that there are limitations associated with this study. Most significant limitations include: zero placebo control & zero objective measurements of sleep quality (e.g. with polysomnography).

Borbely & Youmbi-Balderer (1988): “Diphenhydramine caused neither an impairment of psychomotor performance in the morning nor a rebound insomnia in the following night.” (R)

- A single oral dose of diphenhydramine (50 mg or 75 mg) was given to 10 young healthy adults.

- Subjective sleep parameters and motor activity during bedtime were investigated.

- A placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover design was used.

- Self-ratings of sleep latency were consistent with a mild hypnotic action – but none of the subjective sleep parameters differed significantly from placebo.

- Motor activity was generally increased on nights in which the drug was administered.

Rickels et al. (1983): “This study supports the use of 50 mg diphenhydramine as an OTC sleep aid in the treatment of temporary mild to moderate insomnia.” (R)

- 111 mildly-to-moderately insomniac patients participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study to determine the effect of diphenhydramine as a sleep aid.

- A 2-week crossover design was employed in which all patients received both diphenhydramine and placebo for one week each.

- The diphenhydramine dosage was 50 mg per night at “bedtime.”

- Results indicated that diphenhydramine improved various sleep parameters (including sleep latency) to a greater extent than the placebo control.

- Patients on diphenhydramine reported feeling more restful the following morning and patients preferred the diphenhydramine over the placebo despite experiencing more side effects.

Cooper et al. (2015): Only naproxen sodium (440 mg) & diphenhydramine (50 mg) combination improved sleep latency and sleep maintenance relative to standalone diphenhydramine (50 mg) and standalone naproxen sodium (440 mg). (R)

- Tested a combination formula (naproxen sodium & diphenhydramine) versus standalone diphenhydramine for the treatment of induced transient insomnia involving “dental impaction pain” (following molar removal).

- This was a 2 study, 2-center, randomized, double-blind, and double-dummy trial.

- The first study involved 712 patients and second study involved 267 patients – all experiencing pain from molar removal.

What can we learn from this study?

Perhaps the combination of naproxen sodium (440 mg) & diphenhydramine (50 mg) is more effective than standalone diphenhydramine for the treatment of insomnia associated with dental impaction pain.

This makes logical sense given that naproxen sodium targets the pain and diphenhydramine induces a sedative/hypnotic effect. There could theoretically be some additional sleep enhancing effect from naproxen sodium via lowering inflammation – but this is unlikely significant.

Overall the results of this study make logical sense: painkiller + hypnotic = helps with transient insomnia resulting from dental pain more than either as a standalone.

Seems like an unnecessary study to me given the fact that these were predictable outcomes, however, this substantiated the combination’s clinical safety and efficacy.

Does this prove that standalone diphenhydramine is ineffective for insomnia? No. It just shows that among patients with “pain” (resulting from something like a dental procedure) – it’s necessary to treat the pain (naproxen) while inducing sleep with a hypnotic (diphenhydramine).

This is beneficial in the sense that we know naproxen is safe with diphenhydramine unlike other common pain-reducing agents (e.g. acetaminophen).

What’s the scientific consensus of diphenhydramine for sleep?

There haven’t been many high-quality studies investigating the safety and efficacy of diphenhydramine for the enhancement of sleep or the treatment of insomnia.

A systematic review concluded that there is no robust scientific evidence to support the clinical safety and efficacy of diphenhydramine for the treatment of insomnia.

Benefits reported in a couple of isolated studies included: increased sleep efficiency and fewer nighttime awakenings – relative to placebo. However, these “benefits” weren’t replicated in other research.

Other studies found that diphenhydramine was no better than a placebo in the treatment of insomnia or in the modulation of sleep architecture.

Moreover, because diphenhydramine: (1) caused significantly more adverse events (e.g. next-day psychomotor impairment) than a placebo control; (2) has numerous interaction with other drugs & medical contraindications; (3) may induce rapid tolerance onset; and (4) may not be safe long-term (e.g. increased dementia risk) – it cannot be clinically endorsed as a useful intervention for insomnia or as a sleep enhancement agent.

Benefits of diphenhydramine for sleep & insomnia (Possibilities)

- Higher quality sleep: Fewer nighttime awakenings and/or sleep disturbances. This may be due to increased sedation (relative to baseline) and/or lower levels of anxiety.

- Allergies & insomnia: Diphenhydramine is effective for the management of histamine-mediated allergies. Among persons with allergy and insomnia – diphenhydramine may be a temporarily useful intervention.

- Decreased sleep onset latency: Some individuals (e.g. those with primary insomnia) may find that diphenhydramine reduces the amount of time it takes to fall asleep.

- Effective (?): A subset of people find diphenhydramine [subjectively] effective for sleep enhancement and insomnia management – particularly when used intermittently.

- Fewer awakenings: One small study showed that diphenhydramine significantly reduced the total number of nighttime awakenings relative to placebo.

- Less mental chatter: Those with anxiety may have racing thoughts that keep them awake or that contribute to “middle” insomnia (waking up but unable to fall back asleep). Diphenhydramine’s simultaneous modulation of histamine and acetylcholine receptors may help reduce thought speed/mental “chatter.”

- Longer sleep time: Some people may sleep for a longer duration with diphenhydramine due to its sustained sedative/hypnotic effect (often causing grogginess & fatigue the morning after administration).

- Increased sleep efficiency: One study found that diphenhydramine increases sleep efficiency.

Drawbacks & risks of diphenhydramine for sleep & insomnia (Possibilities)

- Adverse reactions: Sedation, sleepiness, dizziness, disturbed coordination, epigastric distress, thickening of bronchial secretions, urinary retention, confusion, delirium, constipation, etc. DPH is metabolized by CYP2D6 enzymes and has 28 “major” drug interactions – one of which is acetaminophen.

- Brain fog, cognitive deficits, grogginess: Diphenhydramine can cause a combination of brain fog, cognitive deficits, and grogginess – often lasting the entire morning-after or day-after administration. This might be unacceptable for individuals who require normal cognition for work-related tasks during the day.

- Cough-related insomnia: Diphenhydramine was NOT more effective than a placebo in providing nocturnal symptom relief for children with cough and sleep difficulty as a result of an upper respiratory infection. (R)

- Cholinergic rebound syndrome: Anyone using high doses of diphenhydramine for sleep may experience cholinergic rebound syndrome with symptoms such as: agitation, confusion, hallucinations, insomnia, drooling, and extrapyramidal reactions.

- Duration of effect (?): The duration of diphenhydramine’s effect varies depending on individual pharmacokinetics (which are typically age-related). The medication “lasts” longer in older adults than young adults.

- Rapid tolerance onset (?): A randomized, double-blind, crossover study showed that tolerance develops quickly to the effect of diphenhydramine when administered twice daily at a dosage of 50 mg – for 4 consecutive days. (R)

- (By day 4 the levels of sleepiness achieved with diphenhydramine did NOT differ from those associated with placebo.) Tolerance onset occurred after 3 days.

- (It’s possible that this study does not reflect actual rate of tolerance onset in those using it for sleep due to the fact that most people take diphenhydramine just once per night.)

- Long-term effects: There are numerous studies suggesting that long-term regular usage of antihistamines is associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and brain atrophy (e.g. dementia).

- Memory deficits: Usage of diphenhydramine may interfere with the formation and retrieval of memories. Working memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory may all suffer.

- Nightmares & vivid/weird dreams: Some individuals report nightmares and/or bizarre/vivid dreams while using diphenhydramine. This may cause more frequent awakenings in some cases.

- Neuropsychiatric reactions: The combination of H1 inverse agonism and mACh receptor antagonism may cause some adverse neuropsychiatric reactions such as anxiety, depression, agitation, etc. – in susceptible individuals.

- Not medically endorsed: The most recent systematic review concluded that evidence does NOT support the safety or efficacy of diphenhydramine for sleep/insomnia. For this reason, insomniacs should consider safer and more effective alternatives.

- Psychomotor impairment: Physical abilities such as movement, coordination, dexterity, strength, speed, etc. may all be impaired after using diphenhydramine for sleep. For this reason, you should avoid specific tasks (e.g. weight lifting, driving, etc.) if experiencing impairment.

- Residual (next-day) effects: These can include fatigue/lethargy, psychomotor impairment, brain fog/cognitive deficits and overall impaired functioning. Users of diphenhydramine should not operate heavy machinery (e.g. drive motor vehicles) if residual effects are present.

- Unnatural sleep architecture (?): One study found that diphenhydramine significantly increases REM latency and reduces total % spent in REM. Whether this is significantly detrimental remains unclear. (Other studies found no differences in sleep architecture with DPH vs. placebo.)

- Unlikely to override/offset caffeine: Many people have “insomnia” that would completely go away if they stopped drinking caffeine. These individuals make every last excuse to avoid giving up caffeine but complain about their insomnia and medications not helping with sleep. Diphenhydramine is unlikely to fully override the effect of caffeine for those with caffeine-related insomnia.

- Withdrawal symptoms: Individuals who use diphenhydramine regularly (on a daily basis) for longer than 3 days may develop physiological tolerance to its effect. Furthermore, stopping the medication may cause withdrawal symptoms (possibly including rebound insomnia).

- Worse sleep (?): Some people experience a worsening of sleep under the influence of diphenhydramine (characterized by poorer sleep quality and shorter total sleep time).

What’s the maximum effective dosage of diphenhydramine for sleep?

According to research by Kudo & Kurihara (1990), there’s zero additional hypnotic benefit derived from administration of diphenhydramine above a dosage of 50 mg. Dosages above 50 mg also caused significantly more adverse events.

There’s no “optimal” dosage of diphenhydramine for sleep (this is somewhat individualized). One study found relatively similar benefit of diphenhydramine at 12.5 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg – with slightly greater benefit at 50 mg than the other 2 intervals.

Research suggests that dosages of diphenhydramine up to 50 mg are relatively effective and safe for individuals without medical contraindications when used as directed.

How I discovered diphenhydramine for sleep & insomnia…

I accidentally discovered how well diphenhydramine can work as a sleep aid while dealing with some sort of skin allergy.

I had extremely itchy skin following usage of a new laundry detergent and took 25 mg diphenhydramine.

Within the hour I became sedated/zombified despite the label reading “non-drowsy” (LOL).

I think I administered it at around 7 PM and I was K.O.’d by 8 PM.

When I woke up the next morning, over 8 hours had passed and subjectively I felt as though it was the best sleep I’d gotten in years.

The one thing I can say though is that it can cause some super weird dreams… (or at least in my experience it does).

I have dreams that somehow manage to incorporate people from childhood that I would’ve otherwise never thought about.

How I use diphenhydramine for sleep…

Infrequently (randomly): To prevent tolerance onset and side effects associated with long-term/chronic usage (e.g. cognitive decline).

~1 hour before sleep time: Seems to kick in within 30 minutes for me and I become extremely sedated within 45 minutes such that I want to sleep. (This effect is NOT the same if I’m caffeinated though.)

Meditation & relaxation: While using diphenhydramine I like to engage in relaxing activities like meditation in bed if my goal is sleep. Overuse of electronics (e.g. cell phone, computer, etc.) may interfere with sleep onset in some cases.

Lowest effective dose: For me the lowest effective dose of diphenhydramine for sleep is 25 mg. I’ve tried both 6.25 mg and 12.5 mg and neither delivered a significantly beneficial effect. I have not tested doses above 25 mg because I have no reason to – the 25 mg works fine.

Standalone: No caffeine, no alcohol, no melatonin, etc. I do NOT use any other medications, drugs, or supplements on the same day as taking diphenhydramine. I have occasionally tried diphenhydramine on days when I drink too much caffeine and it does NOT work as well. I’ve also tried mixing it with other agents like melatonin and valerian, etc. – but it doesn’t work nearly as well in this case either (for me at least).

Should you use diphenhydramine for sleep & insomnia?

Ask a medical doctor whether it’s safe and/or likely to be effective for your specific case.

Certain individuals may: (1) be taking medications that could cause severe interactions with diphenhydramine OR (2) have medical conditions that are contraindicated with diphenhydramine.

If you require pharmacological intervention for insomnia – there are many other (arguably superior) options to consider [including H1 inverse agonists/antagonists if these are your preference].

Have you used diphenhydramine for sleep & insomnia?

If you’ve tried diphenhydramine for sleep or use it often, consider sharing a comment about your experience.

In the comment consider including things like:

- Why you use diphenhydramine

- Frequency of usage

- Dosage administered

- Co-ingested medications, drugs, supplements (?): Including caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol.

- Tolerance onset (?): If you use diphenhydramine regularly for sleep enhancement or insomnia – have you noticed any tolerance to its effect? Have you become dependent on it to get sleep?

- Medical conditions (?): May influence the efficacy of diphenhydramine for insomnia.

- Sleep onset latency (estimated)

- Subjective sleep quality with diphenhydramine

- Total sleep time (estimated) with diphenhydramine vs. without

- Comparison to other antihistamines or sleep medications that you’ve tried